|

|

| Celeb Tattoos | Facts & Stats | Designs & Symbols | History | Culture | Links | Tattoo Galleries | Contact | |

|

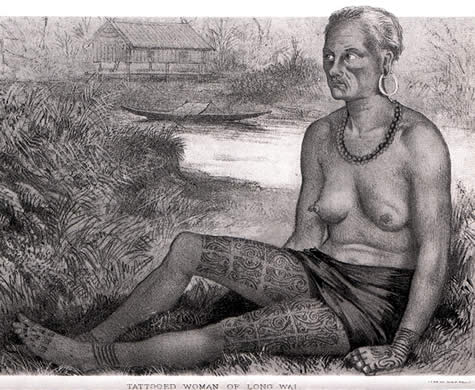

ANCIENT TATTOOS: Theories of Heaven and Earth Article © 2009 PJ Reece Borneo Archeological evidence has shown that ancestors of some contemporary tribes have lived in Borneo for 50,000 years. It's impossible to determine how long tattooing has been important to the Dayak people, but without doubt headhunting and tattooing were closely connected. Some of their myths and legends are so primal that we can't help but imagine that they must have emerged from a time beyond any reckoning. Consider their belief in the power of the tattoo to navigate a course through the Afterlife. As the soul ventured up the river that ran through 'Sebayan', the Land of the Dead, the tattoo lit the way. This was a journey that only the most heavily tattooed warrior could complete. Without their tattoos, the deceased would never find the longhouse of his most heroic ancestors. Among the Kayan tribe runs the belief that after death the completely tattooed woman will be allowed to bathe in the mythical river called Teland Julan, and to gather pearls found on the river bed. Incompletely tattooed women can only stand and watch from the riverbank, while the un-tattooed will not be able to approach the shore at all. For other Dayak tribes like the Iban, the tattoo had an equally vital function while the individual was still living -- they ensured the gods would recognize him. In a jungle realm so very rife with troublesome spirits, an Iban who was invisible to his gods was virtually doomed.

In cultures without a written language, beliefs such as these are impossible to track backwards in time to prove their ancient origins. However, their stories have the power to catapult our imaginations to the very beginnings of culture, where we're faced with the astonishing possibility that myth -- emerging from mankind's collective unconscious -- might actually precede culture. If that's true, then 'tattoo' and other indigenous rituals were a response to deep-seated instincts. Tattoos were a way to acknowledge the mythic realms, which, by their subtle nature could never be fully grasped. Even in our modern society, we support our 'myths of authority' by dressing up our priests in robes, our soldiers in uniforms, and our judges in wigs. But in primitive cultures where people spent their lives mostly naked, it's the body that must be changed. In the Beginning Was the Image Where the ancients identified with an image - as the Iban did with the frog, scorpion and centipede for example - and where Egyptian women did with the god Bes -- and the Pazyryk horsemen with their stylized deer tattoos -- these were a form of communication with the spirit world. Pictures and symbols are an especially efficient medium of communication, since they don't require the intellect to process them. Our dreams prove that without a doubt. In fact, we humans have such a ready stockpile of mental images, stories, memories and symbols at our disposal that it's not far-fetched to suggest that 'thought' is actually built upon a much more profound domain of 'poetic' substance. Archetypal psychologist, James Hillman, says it best: "In the beginning is the image." "Man is primarily an image-maker," says Hillman, "and our psychic substance consists of our images; our experience is imagination." This theory challenges those who would decry everything but so-called concrete reality - but physics has shown us that hard reality is an illusion, a limited point of view. Through the ages, mystics have been preaching the same thing, trying to trick us into perceiving existence as the 'formless' reality they insist it is. Another exponent of the 'imaginal' school of thought is Roberts Avens, who adds, "It has been observed that the basic disease from which our culture may be dying is man's disparagement, if not vilification, of images and myths -- accompanied by his faith in a positivistic, rationalistically ordered and dirt-free civilization." Attention to this 'imaginal realm' has been ignored by traditional psychology in favour of studying the lower dynamisms of survival, sex, and power. Powerful instincts they certainly are, but the ancients, by virtue of their unashamed relationship with invisible realms, suggest that another instinct is at work in the human organism -- the instinct for transcendence. Can we understand human behaviour without acknowledging it? Arianna Huffington, author of The Fourth Instinct, thinks not.

Tattoos in the service of human evolution, it's a bold claim. To believe that images speak to us from our soul is wilder speculation yet. Herman Melville, the great American writer of the 19th century (Moby Dick, 1851), must have wondered about such a 'fourth instinct' when as a young man he jumped ship in the Marquesas Islands. He found himself in one of the richest tattoo cultures in the world. Later, while creating his fictional harpooner, Queequeg, he ascribed to him a kind of transcendental tattoo art:

In recent centuries, no tattoo tradition developed more lush and mythic imagery than the Japanese. Heroic and religious motifs were combined with symbolic animals and flowers against a backdrop of waves, vegetation, clouds and lightning bolts. These body-covering designs originated in the wood block art traditions of the 18th century. But for a millennium before that -- while Japan was taking its cultural cues from China -- tattooing had become punitive, used to mark convicts and outcasts. Chinese texts make the first mention of Japanese tattoos. From 297 A.D. comes this quote: "Men young and old, all tattoo their faces and decorate their bodies with designs." Further reference was made to a young lord who "cut his hair and decorated his body with designs in order to avoid the attack of serpents and dragons. The Wa (Japanese) who are fond of diving into water to get fish and shells, also decorated their bodies in order to keep away large fish and waterfowl." The Chinese observers would have viewed all this very much as a sign of barbarism. As in other cultures, the evidence of earlier tattooing in Japan is suggested in the discovery of clay figurines. These 'dogu' have faces painted or engraved to represent the kind of tattoo marks later found on the mouths of the indigenous women of Japan, the Ainu. So, how far back do these figurines date? The oldest of them have been recovered from tombs that date to 5000 B.C. Some would confidently extrapolate Japanese tattoo culture backwards to the beginnings of the Jomon Period, back to Paleolithic times, roughly 10,000 B.C. Although these ancient tattoo designs vanished from Japanese culture, they can be seen today in the indigenous populations of the South Pacific. |

|

|

|

|

| Celeb Tattoos | Facts & Stats | Designs & Symbols | History | Culture | Links | Tattoo Galleries | Contact | |

Japan

Japan