HOME

TATTOO BLOG

SYMBOLS & DESIGNS

CELEBRITY TATTOOS

THE TATTOO PROJECT

TATTOO PHOTOS

TATTOO MUSEUM

TRIBAL TATTOOS

TATTOO FACTS

TATTOO LINKS

Foreward

SCHIFFER TATTOO PROJECT BOOK

But, to me, as a magazine editor, the biggest change in the tattoo landscape wasn’t just the incredible influx of new shops or the crowning of new royalty among the tattoo hierarchy; it was the photography. When I took over, the magazine’s staff photographer was Jan Seeger, the talented wife of tribal tattooist Trevor Marshall. She was responsible for photographing the, then, limited convention scene and filling the pages with images of pretty girls and their ink. I had never seen photos this bold or thoroughly dramatic. Placing her tattooed models on a simple, three-foot stool with a monochromatic, black backdrop, a basic key light and a fill, her images leapt off the page and immediately inspired me to interweave the magazine with an ongoing gallery of similarly luscious tattoo pictures. Over the next fourteen years, I worked with all the top tattoo photographers, the major lenspeople who covered the conventions for their respective magazine. Billy Tinney shot for Tattoo. Bill DeMichele and Richard Todd worked for International Tattoo Art and, along with Charles Gatewood, Dianne Mansfield and Hell’s Angel Steve Bonge, this small handful of photogs pretty much led the field. But I sought something a little different. While Seeger was a master of her technique, I felt it was important to work inside the industry and find someone to wade though the backstreets and sewers, someone who could capture the authentic rough-and-tumble of this burgeoning art form. While I admired Seeger’s work, I felt more comfortable with my own gonzo journalistic team that included Maurice Pacheco. Maurice and I hit it off immediately. He was a member of the four-person cadre that helped plan my very first issue. Maurice knew the artistic landscape, partied with the current players and wasn’t afraid to get his hands dirty. He was invaluable in capturing the current artists with a special mix of portraiture and candid exuberance. His photos not only leapt off the page, they actually spoke. The expressions on the faces, their hand gestures, the way the models stood in front of the camera—he made his subjects and all their crazy, pretentious idiosyncrasies come alive. Enter Bernard Clark. Clark was from a small town in Canada, but his technique and vision were universal. I remember that he wrote me a letter asking to publish a selection of his tattoo photos. I loved his work: clean, crisp and personal. And, since I had some tattoo events to cover for the magazine and Maurice had left to photograph the rock & roll scene, Bernard became my new compatriot for various convention features, shop stories and, in 2001, an international tattoo gathering hosted by Petelo Sulu’ape in Apia, on the island of Upolu in Samoa. From then on, I worked closely with Bernard at all his photo sessions, running around, gathering models for him to shoot and making suggestions about how to frame a particular model (a quality of working together not especially prevalent with the other photographers in the business). Bernard was fantastic to work with, never let me down and, sometimes, he’d go ahead and shoot a scene I had nixed, so his conscious didn’t bother him, in the morning. A stickler regarding detail, a Boy Scout when it came to honesty and his completely selfless dedication to going the extra mile, Clark was my good-right-arm for the next twelve years. And then came Vince Hemingson. I first laid eyes on Vince Hemingson in Samoa. It was the fall of 1999. I was there with my friend and photographer Bernard Clark covering Paulo Sulu’ ape’s unforgettable and historic Tattoo Millennium Convention on the island of Upolu. The event was held to commemorate the day, a thousand years ago, when twin sisters, Tilafaima and Taima, swam all the way from Fiji, bringing their hand-wrought tattoo tools―the au, the sausau―to the beach at Faleaséela. To celebrate this glorious moment in Samoan history, Paulo invited several of the world’s most prestigious and learned tattoo artists to a convention and party. The seventy or so participants came from Denmark, The Netherlands, New Zealand, England, Germany, Canada and the United States. Because of the incessant heat and humidity, all of us, including the women, wore traditional, thin cotton lava lavas around their waists. Most of the men went shirtless or sported sweat-soaked tank tops. We were a very scruffy bunch. Lots of threadbare sandals and rubber flip-flops. The ladies wore sun-bleached halters and fanned themselves with magazines. And that’s when I saw Hemingson. I had never met him before, so when he stepped from the thick, green jungle foliage like a matinee idol―hair slicked back, perfectly groomed moustache and goatee―marching toward us like a man on a mission, I was more than intrigued. I remember that, while the rest of us looked like castaways, Hemingson wore a perfectly matched Bermuda short and a khaki shirt ensemble―emblazoned with, I might add, a bright-red, hand-stitched logo centered neatly above the breast pocket. He reminded me of Jon Hall in the T.V. series Ramar of the Jungle. Yes, there he was, Mr. Vanishing Tattoo himself, Vince Hemingson. If memory serves me right, Vince had just arrived from a scouting party in another remote location, Borneo, I think, where he was gathering info for a National Geographic television series. It was all part of his research, gathering cultural information about tribal tattoo customs that were, because of the inevitable march of time, quite simply, disappearing. Samoa, because of its long tattoo history, was perfect for one of Vince’ episodes. That’s why he came to Apia. But Vince did more than look the part. He has spent more than a decade searching and researching every aspect of this extensive and fascinating subject. Not only did he get his show aired by National Geographic (and won a mantle full of awards doing it), Vince also created the world’s top-rated tattoo website, hosting over a million viewers a month. Yes, vanishingtattoo.com is both the industry’s premiere website and a tribute to Vince’s absolute dedication, skill and perseverance. And it all exists thanks to a love so passionate that it has given birth to the very volume you hold in your hand, The Tattoo Project: body. art. image. Vince demonstrated a keen eye for quality, a heartfelt love for tattoos and an unerring persistence in making his own, personal dreams and aspirations a rock-solid reality. Which is why, when Vince invited me to come to Canada and write about his latest adventure, The Tattoo Project, a tattoo extravaganza featuring the work of nearly a dozen, local Vancouver, B.C. photographers, I, without reservation, said yes. * * * Arriving in Vancouver, I was all ready to dislike the photographers. After all, I knew the best in the business— DeMichele, Mansfield, et al.—and none of them were here. Being a Vancouverite and personally connected to the regional art scene, Hemingson kept the cast of characters local and culled the enormous list of model applicants down to a manageable one hundred pretty girls and winsome gentlemen. Eleven photographers, three days of shooting. Clearly, the logistics of this endeavor were staggering. Every room on every floor of the Vancouver Photo Workshops’ nondescript building on a commercial street down by the fast-flowing waters of the Strait of Georgia was utilized. Studios, partitioned anterooms, hallways, basements, carports, stairwells, you name it. Vince told me that getting all the photographers to the right place at the right time was “like trying to corral a herd of chickens.” Having a backyard of chickens myself, I understood.

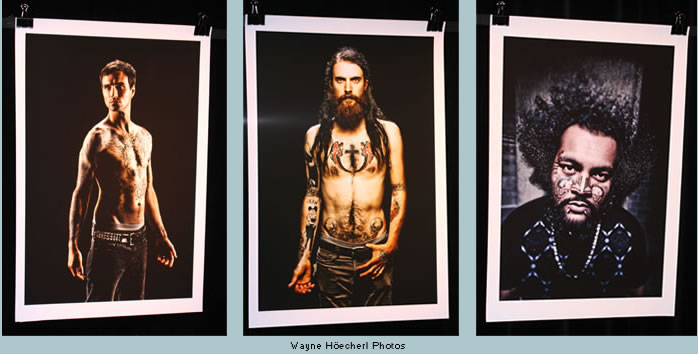

Soon after my arrival, I grew comfortable with the surroundings and began watching how each photographer related with their models. I knew how my industry friends worked and now it was time to find out how these “outsiders,” people who do not ordinarily photograph tattooed models, would fare. In the beginning, how they talked to each model was sometimes jarring and they, to my way of thinking, overshot. They made way too many clicks of the shutter. But I remembered that, in shooting for a magazine, Bernard and I got used to “editing in the camera” and only shooting people and poses that we thought would end up in magazine. Tinney and the rest would sometimes photograph hundreds of subjects during a weekend. For us, forty was a lot. The men and women at the Workshop had the same hundred models each and, while I thought they wouldn’t be able to snap them all, especially spending such a long time with each one, but I was wrong. This extra time resulted in a growing familiarity with an unfamiliar subject, namely, tattoos. The surprise of the day was Hemingson mentioning an appointment with a model, who was so excited about the project, that she flew in from New York City. I knew Vince was an expert videographer, but his including himself in the cadre of local talent seemed to me a busman’s holiday, a way to include himself in this elite company of local lenspeople. Time would tell. The proposed end product of this weekend of click-click-click was a gallery show, a television special and a coffee table book. Since this is a foreword for that very publication, we can guess what happened. Tuned into every aspect of producing and promoting this event, Hemingson hung, six months later, his gallery show at Performance Works on Granville Island. This was the first time I viewed the photographs. Eleven photographers shooting an unfamiliar subject, a lot of planning, a lot of talk, but what would it look like? Thank heaven, I thought, there’s free beer. The photographic fruits of the four-day photo session were collected, culled, sorted, divided, prepared and mounted on the black-velvet walls of a high-ceilinged gallery located amidst the public market, yoga studios, oyster houses and slow-moving traffic of colorful Granville Island, Vancouver’s “town square.” The perfect place to celebrate diversity. And that’s what Hemingson did, by not only making a significant visual statement but gathering together an extraordinary number of partiers to toast the event. “I hope to bring in 400 people for opening night,” he told me, a week or so before the big show. “There’s stories in all the local newspapers. That ought to help,” and help it did. Due to Hemingson’s obvious marketing skills, nearly a 1000 people attended the Friday night opening and the football-field-sized gallery hall was packed with happy sardines for a show that included special guests Lyle Tuttle, yours truly and Melody Mangler’s Screaming Chicken Burlesque Revue. All that and a free drink ticket for everyone in attendance. It was cold outside, but, inside… it was time to par-tay! I must have seen a zillion tattoo photographs during my years editing a tattoo magazine, so I am, admittedly, quite jaded. But when I entered the main doorway into the gallery, I was impressed. To my right, were brightly illuminated, three-foot-by-four-foot, full-color images on snow-white photographic paper by Wayne Höecherl. A sensational display against the black-velvet background. Held in place by black and chrome alligator clips, this first-thing-you-see placement (mounted by gallery architect and curator Penny Lane Shen) let us know we were in for something wonderful. As with most of the other artists’ work, Höecherl’s images were exhibited in their own cubicle, with walls in front and to either side. The lighting was superb. The photographs, especially Höecherl’s, glowed in space, enriched by the super-perfect focus and dramatic color palate of the body art.

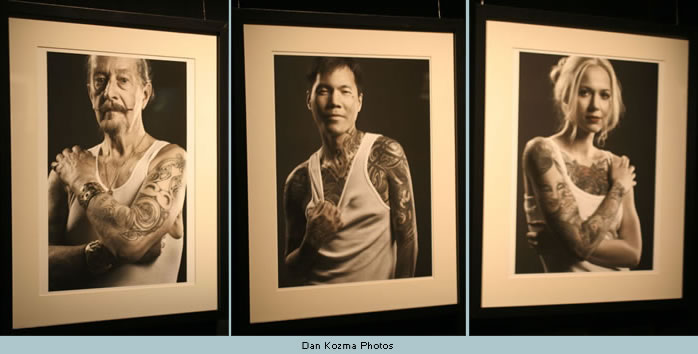

To be honest, I was expecting a lesser result from these photographers. But what these photos lacked in the subtle interplay between the models and their tattoo work, it was more than compensated by the sheer dramatic effect that Höecherl achieved in his eye-opening display by the main door. Just as I was admiring the method of displaying the images (white paper, metal alligator clips), I turned the corner and everything changed. Mounted with standard white mats and simple black frames, these muted, black & white images by Dan Kozma looked hand-painted, merely suggesting color, quietly, without letting it dominate. Shot from the waist up, these close-up portraits captured the models energy, but because of their sheer size and inyour- face focus, the subjects stared, grabbed your eyes and wouldn’t let go.

The third cubicle presented several rows, left to right, of small, black & white Polaroid images. Set in identical black frames with white matting, these images were fascinating, and a couple caught my eye, but after the dramatic presentations of Höecherl and Kozma, I pretty much drifted past these and, once I caught the image of the enormous, well-lit, single collage out of the corner of my eye, to my left, couldn’t wait and had to move on. What I saw was one of my favorite pieces in the whole show: Spencer Kovats’ four-foot-by-five collection of before-and-after shots of sixty (six high by ten wide) photos of men and women, one wearing street clothes and, next to it, one with their tattoos exposed. It’s a simple idea, but it really, really worked. The sheer joy of seeing thirty people literally come alive, when their ink was exposed, was a powerful and perfectly conceived statement of the significance and tonic of joy that tattoos add to an individual’s life. The ink was the perfect party makeup. I’ve not seen this idea executed so well and assembled in such a visually rewarding fashion. This was one piece of art that I definitely wanted to take home.

In the middle of the back wall was another powerhouse display. Although Hemingson’s appearance at the Photo Workshop in May was, I thought, merely his make-a-wish chance to participate with some of Vancouver’s best shooters (kind of a busman’s holiday), the results of his photo sessions were not only equal to his compatriots’, they were some of the exhibit’s very best work. Displayed as full-color transparencies, backlit and gallerymounted, shadow-boxed away from the wall, Hemingson’s photographs not only supplied a welcome splash of color and illumination between two collections of relatively miniscule images (Kovats on the right and Johnathon Vaughn to the left), but the contrast against the blackness of the wall itself shone like a neon sign, beckoning from the darkness and inviting viewers into the deep recesses of the room itself. His double panel, especially, was the perfect counterpoint to the repetitive sizes and shapes of the images posted around the rest of the room. Without belaboring the point, it is clear that Hemingson not only knows how to produce a stunning show, he was a significant contributor as well, this Gallery Exhibition marking his emergence as an extraordinarily talented and gifted photographer. Having known Vince now for more than I decade I am excited to see where this next chapter in his already lengthy and impressive artistic career takes him.

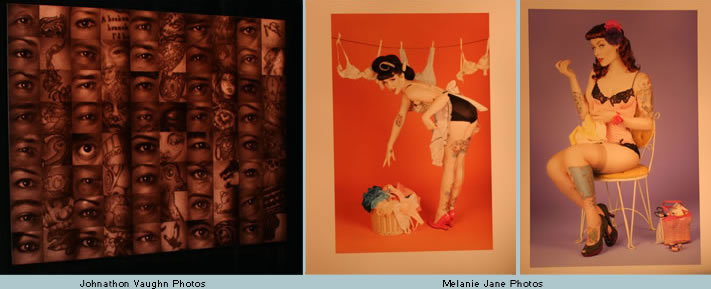

To the left of Hemingson, was the brilliant, single-panel, sepia-toned collection of eyes and art by Johnathon Vaughn. He’s the guy I thought was taking passport pictures. In fact, I didn’t have much faith that his place in a gallery show would be worth viewing. I was wrong. Assembling a collection of forty right eyes and a partial section of each model’s favorite tattoo doesn’t sound like a traffic stopper, but it was. For me, it got down to the nitty-gritty, the essence of what tattoo is all about. One eye. One tattoo. Magnetic. It was especially fun to find Vince’s eye and mine, too, among the rows and rows of pictures. It wasn’t great tattoo art and it wasn’t great portrait art, but, of all the displays on all the walls, this was the one that I kept coming back to see, again and again.

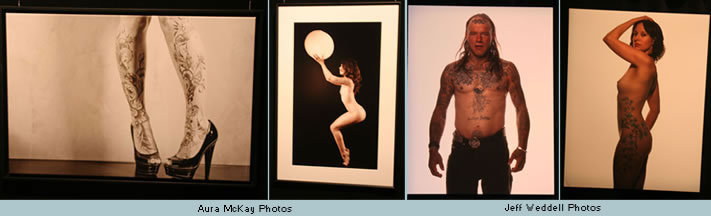

Melanie Jane’s pinup photos were to the left, on a wall that was brightly lit with overhead spots. Costumed and posed to replicate 1950s pinups in scanty, period underwear doing dishes and ironing isn’t a new idea, Jane should be applauded for taking such a daring departure. A nice contrast to the rest of the exhibition. Aura McKay had a completely different approach. Her photos, each and every one, were different. Here a leg, there a back. Her shots were technically good, and I’m sure the audience enjoyed these high-concept images, if only because they were so different from anything else in the room. I wish there had been more examples of this photographer’s work.

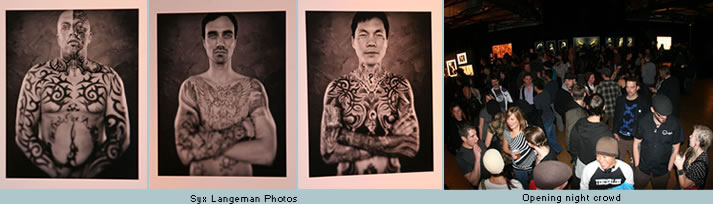

Around the corner from Aura McKay was Jeff Weddell, one of the solid, no-nonsense photographers who carried out the project’s concept most effectively. Rather than adding too much to the pictures, Weddell simply displayed images of people with their tattoos and let the viewers react on their own. Although Weddell’s approach to photographing the models is similar to the photographs by Höecherl and Kozma (just models and their tattoos, without frills or added “concept”), his stark, white backgrounds and soft shadings were a unique contribution and welcome contrast to the brighter, more theatrical images of some of the other contributions to the exhibit. His models were the most introspective. Syx Langemann took a different tact altogether. His black & white images were the perfect counterpoint to the rest of the exhibit. Focusing closely on the details of each model’s face and obscuring the tattoos themselves by using a tilt and shift camera lens, he rendered the tattoos in a cloudy, ethereal, out-of-focus manner. A fun departure from the rest of the work displayed and a definite standout in the uniqueness category. A great idea done with excellent execution.

Wrapping up the show were some fine images of the guest of honor, Lyle Tuttle, from his early days (the volunteers dispensing beer and wine were stationed nearby, in the middle, behind the stage). To the right, finishing off with a splash of color, were portraits by Rosamond Norbury, a highly professional lens master utilizing richly-colored backgrounds to turn the predictable subject matter into glorious art. While Höecherl, Kozma, Langemann and Weddell posed their subjects in straightforward, here-we-are, take-a-look poses, and Hemingson treated his subjects in a more respectful, painterly fashion (after all, he was the one photographer with a significant understanding of the “tattoo as fine art” concept), Norbury tended to pull more personality from her images, by adding her own technical body-English. More of the same and yet so different. And who was the winner? The thousand first-night visitors who had an opportunity to share in a dream that Vince Hemingson brought to life before their eyes, that’s who. This was not an easy project to actualize. Knowing how these far-reaching projects go, I’m sure there were lots of backroom shenanigans and shows of artistic temperament that Hemingson had to deal with, not to mention the obvious expense in producing a showcase that one critic remarked was “equal to anything in New York galleries.” More than one person connected to Vancouver’s art and photography worlds told me that the opening night to the Tattoo Project: body. art. image. Gallery Exhibition was a seminal event. A justified compliment, to be sure, and all the more incentive to stay tuned to the future of this project (Vince has already marketed a calendar, which sold like proverbial “hotcakes,” at the event). I have been involved in the tattoo industry and the tattoo community for more than fifteen years. The Tattoo Project is unlike anything else I have ever witnessed. And what to make of this extraordinary coffee table photography book that you now hold in your hands? This, my friends, this is a unique and special collection of works of art. Of unique and special people adorned with body art, each of them a participant in an ancient historical cultural practice. And what else does the future hold for the Tattoo Project? A television documentary special is in the works, and perhaps a film festival entry in the not too distant future? All in the cards, I’m sure. Proving that, with dedication, world-class taste and a love of tattoo, on that Friday night in November, Hemingson and his crew made dreams happen. Whatever else you can say about Hemingson, and you can say a lot, what he does, he does with flair, style and a wonderful sense of “je ne sais quoi” (I am after all writing about the arts in Canada, and French is the other official language). Well done, Vince. Well done. Tres bonne! —Bob Baxter As editor in chief of Skin&Ink magazine for over fourteen years, Bob Baxter guided the publication to a Folio Magazine Editorial Excellence Award, making it America’s most respected and educational body art publication. He currently edits and writes a Daily Blog at www.tattooroadtrip.com, the ultimate E-zine and resource site for international tattoo artists and collectors. He also has his Tattoo Chronicles series and the 101 Most Influential People in Tattooing right here @ Vanishing Tattoo. To ask questions, make comments or demand an apology, you can email Bob at baxter@tattooroadtrip.com. |

|

By Bob Baxter

By Bob Baxter