| Celeb Tattoos | Facts & Stats | Designs & Symbols | History | Culture | Links | Tattoo Galleries | Contact | |||||||||||

Return of the Headhunters: The Philippine Tattoo Revival

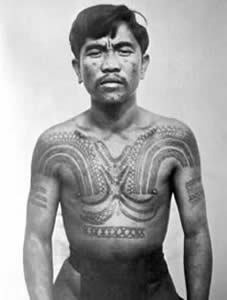

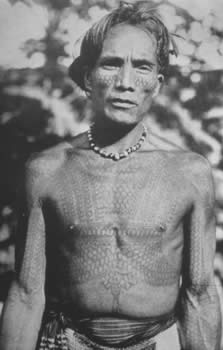

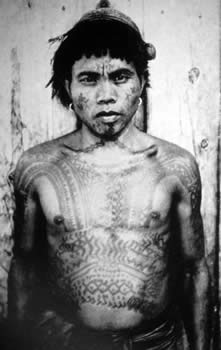

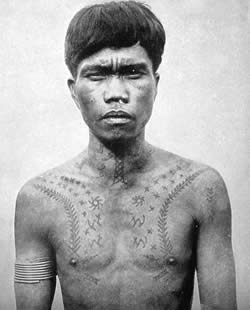

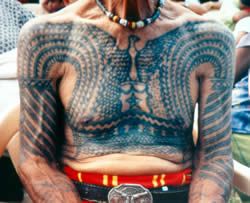

© 2005-2006 by Lars Krutak High up in the terraced rice fields of the Philippine Cordillera mountains, traditional tattooing (batek, Kalinga) among the former headhunters of northwestern Luzon is nearly extinct. Today, you can only see traces of the indelible art in all of its splendor among the Kalinga and maybe one or two other groups living in the area. But back in 1900, just before American authorities outlawed headhunting, tattoo was to be seen everywhere, especially among the Bontoc Igorot, Kalinga, and Ifugao peoples. Bontoc is derived from two local words, "bun" (heap) and "tuk" (top), which together mean "mountains." As they have for centuries, most Igorots live in Bontoc municipality near the upper Chico River basin and in the capitol city of the municipality, Bontoc. The region is bounded to the north by the Kalinga-Apayao province and to the south by the Ifugao and Benguet provinces. Although there is a common language, several villages in the Bontoc region have their own distinct dialect. Generally speaking, the Bontoc Igorots recognized several kinds of tattoos and very often the amount of designs worn by a man was directly related to the proportion of human heads he had taken in the headhunt. The chaklag, usually running upward from each nipple, curving out on the shoulders and ending on the upper arms, indicated that the man had taken a head or, as one writer put it in 1905, "The indelible tattoo emblem proclaims them takers of human heads, nine-tenths of the men in the pueblos of Bontoc and Samoki wear them." Among the neighboring Kalinga to the north, successful warriors (maingor) had tattoos placed at the back of their hands and wrists after their first kill. These striped designs were called gulot, meaning "cutter of the head." Kalinga men who killed two or more men had elaborate patterns applied to their arms and chests called biking, comprised of khaman ("head-axes"), ufug ("centipede scales") and bodies of the centipede (gayaman), which were protective and spiritually charged symbols. The khaman design also covered portions of the torso, back, and thighs and centipede scales crossed the cheeks of the most successful warriors. Sometimes, a human anthropomorph was tattooed just above the navel and small crosses adorned the face, indicating a warrior of the highest rank. Other more simple markings had therapeutic value and were placed on goiters, tumors and varicose veins. Among the Kalinga particular arrangements of centipede scales were believed to ward off cholera.

Traditional Cordilleran Tattoo PracticeThe people of an ató (one of the political divisions of a Bontoc village) could only tattoo when some person belonging to that ató had taken a head. In 1900, the people of Bontoc village maintained "that tattooing may not occur at any other time, and that no person, unless a member of the successful ató, may be tattooed." Tattooing instruments were made from a piece of wood or water buffalo (carabao) horn about 10 cm long and 2 mm thick. At about a sixth of its length it was bent at a right angle and, in the shorter arm, three to five needles were affixed. The needles were laid on the skin and driven in with blows of a wooden hammer at the rate of 90 to 120 taps per minute. Soot from resinous wood such as spruce was used for pigment and rubbed into the wounds, causing the flesh to rise in great welts, which sometimes became infected. Like the Kalinga, in every Bontoc village there was at least one man or woman who was the tattooist (manbatek, Kalinga). One traveler noticed in May 1903 that "there are two such in Bontoc - Toki, of Lowingan, and Finumti, of Longfoy - and each has practiced his art on the other. Finumti has his back and legs tattooed, and the designs were simple. A large double scallop extends from the hip to the knee on the outside of each of Finumti's legs." Like other tribes in neighboring Borneo and New Guinea, Igorot tattooing was considered a serious religious experience. The flowing blood attracted spirits (anito) which could protect or destroy a community if the proper sacrifices were not made. In the eyes of the people, all diseases, sicknesses or ailments, however serious or slight, were believed to be caused by anito and sometimes these malevolent spirits were not completely satisfied until they were offered a human trophy head that would come to hang in the rafters of the ancestral ató.

Loosing Your Head in the PhilippinesThere was little formality to the practice of head-taking. Most heads were cut off with a battle-ax before the wounded man was dead. Not infrequently, two or more men would have thrown their spears into the victim, who was already disabled. If one of the Bontoc warriors at the scene had never taken a head, he would generally be allowed to cut this one from the body, and thus be entitled to the head taker's distinct tattoo (chaklag). (Of course, the tattooing would not take place until the proper arrangements were made for his victory celebration and feast.) However, the head belonged to the man who threw the first disabling spear, and it found its resting place in his ató. If there was time, men of other ató cut off the victim's hands and feet to be displayed in their ató. Sometimes succeeding sections of the arms and legs were cut and taken away, so only the torso was left upon the ground! But the successful headhunter did not always secure his trophy on the battlefield. On March 31, 1908, the respected and popular Ifugao chief Bahatan traveled to a neighboring village to conduct business connected with a new road then in progress. Having accomplished his errand before noon, he was resting under the house of the village chief when a man of a rival clan came up to him. He approached Bahatan with kind words, drawing his blanket closely around his body to conceal his bolo (beheading sword), and offered the chief a betel nut which he then intentionally dropped upon the ground. As Bahatan stopped to pick up the nut the man quickly threw off his blanket and with two well-directed blows of his bolo severed Bahatan's head from his body! The man did not stop to take the head and before anyone in the village realized what had just happened, he slipped away into the grass thickets surrounding the village. Although it is said that no Bontoc man could marry without first taking a head (the man was constantly "teased" by the single women of the community until he had brought back a head for his "bride's prize"), the origins of Bontoc headhunting are recorded in legends: "The people of Bontoc, say their god and culture hero, Lumawig, taught them to go to war. When a very long time ago he lived in Bontoc, he asked them to go accompany him on a war expedition to Lagod, the north country. They said they did not wish to go, but finally yielded to his urgings and followed him. On the return trip the men missed one of their companions. Lumawig told them he had been killed by the people of the north. And thus their wars began to avenge his death." But elders from the Cordilleran region also affirm that there are other more magico-religious reasons for headhunting. These include the desire for abundant harvests of cultivated products, the desire to be considered brave and manly, the desire for exaltation in the minds of descendants, to increase wealth, to secure abundance of wild game and fish, to secure general health and favor at the hands of the women, and to promote fertility in women. However, individual possession of a freshly severed head did not always guarantee such good fortunes. The trophy had to be "activated" through proper ceremony and ritual before it would "release" its spiritual and magical powers. For example, when an Igorot victor took a head, he usually returned immediately to his village. He brought the head to his ató and put it in a funnel- shaped receptacle that was tied to a post in the communal courtyard. The entire ató joined in a ceremony for the day and night. To appease the anito, a blood sacrifice of a dog or pig was made. Afterwards, the young men of the ató danced to the rhythmic beats of the gangsa gong. About 7 o'clock in the morning, the old men of the ató took the head to the river. There they built a fire and placed the head beside it, while the other men of the ató danced around it for an hour. Then, everyone sat facing the river and, as each threw a small pebble into the water, he said the name of the village from which the head was taken. This was to divert the battle-ax of their enemy from their own necks. The head was washed in the river by dunking it up and down by its hair and the party returned to the communal courtyard where the lower jaw was cut from the head, boiled to remove the flesh, to become a handle for the victor's gangsa gong! In the evening the head was buried in the courtyard where it remained for up to three years. Then, it was dug up and the skull, after being thoroughly washed, was placed in a basket with other skulls and hung in the courtyard. The bodies of low ranking warriors unfortunate enough to lose their heads were buried without formal ceremony under the trail leading to the town of the man who took it. But for chiefs who had been beheaded, thousands of mourners may have attended their accompanying funeral ceremonies. Among the Ifugao, these types of funerals usually took place after a search party had located the decapitated body. During the search party's absence, religious ceremonies were performed in every village in the district that was associated with the chief's clan. Shamans invoked the souls of all of their clan ancestors to insure success for the search party. Thousands of the ancestral souls were called upon by name with particular attention being paid to famous warriors and brave fighters of the past. These were counseled to aid those who had gone out to get the head and body and to prevent the enemy from injuring them on their perilous quest. Ifugao shamans also called upon their "tormentor" spirits. The tormentors were urged to strike the enemy warriors with blindness and dizziness and to fill them with fear, so that they would not attack the rescue party. Shamans propitiated these spirits with small chickens, rice wine, betel nuts, and betel leaves. However, great gifts of pigs and other things were promised to the spirits if the expedition proved successful.

A "Contemporary Headhunter"Although instances are occasionally reported of heads being taken from time to time in the Bontoc region, not since WWII were tattooing and headhunting linked, says Ikin Salvador, an anthropologist at the University of the Philippines-Baguio. Salvador, who has been studying the tattooing traditions of the Cordilleran peoples, noted that "Kalinga men were tattooed on their arms and chests for killing Japanese soldiers during the occupation in the 1940s. But tattooing was not simply an aspect of headhunting culture in and of itself." She continued, "Tattooing was a complex rite de passage that also maintained the polity and the Kalinga warrior class (kamaranan). Sadly, however, it is a cultural practice that is rapidly dying. And unless some sort of tattoo revival occurs in the near future, traditional tattooing in the Philippine Cordillera certainly will vanish forever." Today, only a handful of Bontoc and Kalinga men retain their traditional chest tattoos, and among the Isneg, Kankanay, and Ibaloi peoples traditional tattooing is perhaps extinct. According to Salvador, "Many Bontoc designs have been 'invaded' by Ifugao styles lending to an assimilation of tattoo cultures." And among the Kalinga, Salvador has observed that many elders believe that "this generation is too educated and different. They have no interest in the tattoos of the elder generation." Although the living bodies of old men and women - the last repositories of tattoo culture - will soon leave us, there is hope that the tattooing traditions of the Cordilleran peoples will continue to live on among members of the Tatak Ng Apat Na Alon tribe. Established in Los Angeles in 1998, this organization of young Filipino-American professionals has embarked on a historic journey to preserve and revive the ancestral traditions of their peoples. According to co-founder Elle Festin, "We have a beautiful tattoo culture and it is slowly deteriorating. We want to rekindle the spiritual art forms of our ancestors and to inspire our people to believe in the past; because a people without knowledge of their history, origin, and culture are like a tree without its roots." Festin, who wears a contemporary version of a Kalinga bikking, says: "We have a unique cultural heritage and we want to expose its great beauty. We travel to universities, attend cultural events and tattoo conventions in California to educate young and older Filipinos about the roots of our culture. I liken myself to a 'contemporary headhunter' because I hunt heads and educate them whenever I have the opportunity." So far, 100 of the 150 members of Tatak Ng Apat Na Alon tribe ("Mark of the Four Waves") are tattooed with traditional designs inspired by the indigenous peoples of the Philippines. According to Biggs, his tattoos are important for several reasons: "Almost every culture has been documented except our own. My tattoos serve as an opportunity to enlighten other people to an aspect of my culture which receives little attention. Tattooing breaks with the general mold of what is defined as 'acceptable' in the Filipino-American community so, in a sense, I have been educating my peers and even my parents with these tattoos." Another tribe member, Lee-Way, puts it like this: "My tattoos bring me a sense of my people's history. I think the ancestral spirits keep the tradition alive by working through me…so that I can lay this all down for others to experience." Festin, who is practicing to become a contemporary hand-tapping manbatek (tattooist), agrees by stating that "we will begin to regain the consciousness of our ancestor's art as the Tribe increases in number." Obviously, educating the public on the significance of this ancient and meaningful art form is a difficult task. But back in the Philippines, Salvador has made very important strides in that direction. She has organized three recent museum exhibitions focusing on the vanishing art form of Kalinga batek. These exhibitions have served to remind all Filipinos of the richness of the indigenous tattooing cultures in the Cordillera, and to educate those younger generations of Kalinga who have lost touch with their batek traditions. In the fall of 2004, Salvador, in collaboration with Elle Festin, brought a new tattoo exhibition to Berkeley, California and Ann Arbor, Michigan. This captivating exhibit, Signs on Skin, Beauty and Being, provided audiences with an exciting opportunity to witness firsthand the power and beauty of tattoo among the indigenous peoples of the Philippine Cordillera as well as the ongoing batek revival that continues among the members of the Mark of the Four Waves Tribe.

To contact the Tribe

for more information, please visit:

www.apat-na-alon-tribe.com/

LiteratureBeyer, H. Otley |

|||||||||||

Other tattoo articles by Lars Krutak

© 2006 Lars Krutak |

|||||||||||

| Celeb Tattoos | Facts & Stats | Designs & Symbols | History | Culture | Links | Tattoo Galleries | Contact |