|

||||

| Celeb Tattoos | Facts & Stats | Designs & Symbols | History | Culture | Links | Tattoo Galleries | Contact | ||||

|

Back to BERING SEA | Piercing in the Arctic | Vanishing Tattoo Home Tattoos of the early hunter-gatherers of the ArcticBy Lars Krutak Standing sentinel in the frozen waters of Bering Sea, St. Lawrence Island fosters a complex of remarkable tattooing traditions spanning 2000 years. Ancient maritime peoples from Asia first colonized this windswept outpost lured by vast herds of ivory-bearing walrus and other sea-mammals. Bringing with them new advances in hunting technology and material culture, the Old Bering Sea/Okvik and Punuk peoples quickly adapted to their insular environment. As the forces of nature were quite often difficult to master, they developed an intricate religion centered on animism. Appeasing their gods through sacrifice and ritual, these mariners attempted to harness their forbidding world by satisfying the spiritual entities that controlled it. Not surprisingly, tattooing became a powerful tool in these efforts: for at once the pigment was laid upon the skin, the indelible mark served as both protective shield and sacrifice to the supernatural.

This essay focuses upon a comparative analysis of tattooing practices among the St. Lawrence Island Yupiget, the Inuit peoples of Alaska, Canada, Greenland, and tattooed mummies from Europe and Asia. While often dismissed as a somewhat "mystical" and "incomprehensible" aesthetic, Arctic tattoo was a lived symbol of common participation in the cyclical and subsistence culture of the arctic hunter-gatherer. Tattoo recorded the "biographies" of personhood, reflecting individual and social experience through an array of significant relationships that oscillated between the poles of masculine and feminine, human and animal, sickness and health, the living and the dead. Arguably, tattoos provided a nexus between the individual and communally defined forces that shaped Inuit and Yupiget perceptions of existence..

Archaeological evidence in the form of a carved human figurine demonstrates that tattooing was practiced as early as 3500 years ago in the Arctic. Moreover, the remains of several mummies discovered in Bering Strait and Greenland indicate that tattooing was an element basic to ancient traditions. This is corroborated in mythology since the origin of tattooing is clearly associated with the creation of the sun and moon. The naturalist Lucien M. Turner, speaking of the Fort-Chimo Inuit of Quebec, wrote in 1887: "The sun is supposed to be a woman. The moon is a man and the brother of the woman who is the sun. She was accustomed to lie on her bed in the house [of her parents] and was finally visited during the night by a man whom she could never discover the identity. She determined to ascertain who it was and in order to do so blackened her nipples with a mixture of oil and lampblack. She was visited again and when the man applied his lips to her breast they became black. The next morning she discovered to her horror that her own brother had the mark on his lips. Her emoternation knew no bounds and her parents discovered her agitation and made

Ethnographically, tattooing was practiced by all Eskimos and was most common among women. While there are a multitude of localized references to tattooing practices in the Arctic, the first was probably recorded by Sir Martin Frobisher in 1576. Frobisher's account describes the Eskimos he encountered in the bay that now bears his name:

As a general rule, expert tattoo artists were respected elderly women. Their extensive training as skin seamstresses (parkas, pants, boots, boat covers, etc.) facilitated the need for precision when "stitching the human skin" with tattoos. Tattoo designs were usually made freehand but in some instances a rough outline was first sketched upon the area of application. A typical 19th century account provided by William Gilder illustrates the tattooing process among the Central Eskimo living near Daly Bay, a branch of the great Hudson Bay:

Around Bering Strait, the tattooing method reveals continuity in application, as observed by Gilder, yet the pigments employed were more varied. According to the Alaskan archaeologist Otto W. Geist, the St. Lawrence Island Yupiget tattoo artist drew a string of sinew thread through the eye of a steel or bone needle. The thread was then thoroughly soaked in a liquid pigment of lampblack, urine, and graphite. The needle and sinew were drawn through the skin: as the needle was inserted and pushed just under the epidermis about a thirty-second of an inch. These typical tattoo "operations" required several sittings with the tattoo artist. The results were often accompanied by great pain, swelling, and in some cases, infection and even death.

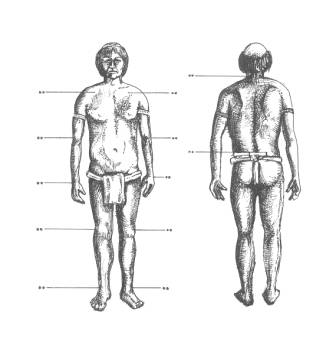

CONCEPTS OF TATTOOING IN THE ARCTIC

From this perspective, it is not surprising that tattoos had significant importance in funerary events, especially on St. Lawrence Island, Alaska. Funerary tattoos (nafluq) consisted of small dots at the convergence of various joints: shoulders, elbows, hip, wrist, knee, ankle, neck, and waist joints. For applying them, the female tattooist, in cases of both men and women, used a large, skin-sewing needle with whale sinew dipped into a mixture of lubricating seal oil, urine, and lampblack scraped from a cooking pot. Lifting a fold of skin she passed the needle through one side and out the other, leaving two "spots" under the epidermis. Paul Silook, a native of St. Lawrence Island, explained that these tattoos protected a pallbearer from spiritual attack. Death was characterized as a dangerous time in which the living could become possessed by the "shade" or malevolent spirit of the deceased. A spirit of the dead was believed to linger for some time in the vicinity of its former village. Though not visible to all, the "shade" was conceived as an absolute material double of the corpse. And because pallbearers were in direct contact with this spiritual entity, they were ritualistically tattooed to repel it. Their joints became the locus of tattoo because it was believed that the evil spirit entered the body at these points, as they were the seats of the soul(s). Urine and tattoo pigments, as the nexus of dynamic and apotropaic power, prevented the evil spirit from penetrating the pallbearer's body. Interestingly, nearly every attribute of the human dead was also believed to be equally characteristic of the animal dead, as the spirit of every animal was believed to possess semi-human form. Men, and more rarely women, were tattooed on St. Lawrence Island when they killed seal, polar bear, or harpooned a bowhead whale (aghveq) for the first time. Like the tattoo of the pallbearer, "first-kill" tattoos (kakileq) consisted of small dots at the convergence of various joints: shoulders, elbows, hip, wrist, knee, ankle, neck, and waist. Again, the application of these tattoos impeded the future instances of spirit possession at these vulnerable points.

It seems that the issue of death, whether human or animal, cast into symbolic tattooed relief important cultural values by which circumpolar peoples lived their lives and evaluated their experiences. But, and for the sake of traveling to a higher level, tattoos also recalled an ancestral presence and could be understood to function as the conduit for a "visiting" spiritual entity, coming from the different temporal dimensions into the contemporary world. For example, in many shamanistic performances in the Arctic, the human body was altered (via masking, body painting, vestments, or tattoo) to facilitate the entry of a "spirit helper." This is not entirely surprising since tattoos and other forms of adornment acted as magnets attracting a spiritual force - one that was channeled through the ceremonial attire and into the body.

From the preceding remarks, it seems that the aesthetics of circles were important in Bering Strait culture, especially when speaking about life and death encounters at sea. Folk-belief suggests that men who were hunting on the water or ice risked serious injury and death by drowning. However, according to Smithsonian archaeologist Henry B. Collins, men specifically risked injury due to walrus attack:

Consequently, it is possible that Bering Strait society fashioned labret-like tattoos to forestall these aggressions. Aspects of folklore suggest that labret-like tattoos recalled in symbolic form the appearance of a killer whale (mesungesak):

Appropriately, these representations of the killer whale ideologically rebuffed the pursuing walrus, in turn, extending a hunter's safe passage through dangerous waters. On the other hand, the art historian Ralph Coe believes that labret-like tattoos mimicked walrus's tusks, especially since many labrets were carved from walrus ivory:

Tattoo foils were not only confined to labret-like tattoos. Instead, men and women were variably tattooed on each upper arm and underneath the lip with circles, half-circles, or with cruciform elements at both corners of the mouth to disguise the wearers from disease-bearing spirits. Paul Silook explained: "[y]ou know some families have the same kind of sickness that continues, and people believed that these marks should be put on a child so the spirits might think he is a different person, a person that is not from that family. In this way people tried to cut off trouble." The multiplicity of "guardian" forms and the various tattoo motifs related to them suggests, in all probability, that specific tattoo "remedies" were believed to differ from individual to individual, or more appropriately, from family to family. An account from a Chaplino Yupiget [Indian Point] visiting Gambell, St. Lawrence Island in 1940, reveals that this was the case, at least in mainland Siberia:

WOMEN'S FACIAL AND BODY TATTOOS

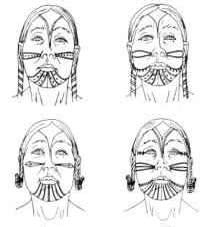

More generally, the chin stripe aesthetic was important to the Diomede Islanders living in Bering Strait. Ideally, thin lines tattooed onto the chin were valuable indicators for choosing a wife, according to anthropologist Sergei Bogojavlensky:

Bering Strait Eskimo myths tell that the spirit and life force of the whale is a young woman: "Her home is the inside of the whale, her burning lamp its heart. As the young woman moves in and out of the house doorway, so the giant creature breathes." Tattoos assured a kind of spiritual permanency: they lured into the house a part of the sea, and along with that, part of its animal and spiritual life. Not surprisingly, an unusual event, such as the capture of a whale by a young woman's father, was commemorated on her cheek(s) by fluke tails, which advertised her father's prowess to members of Asiatic Eskimo society.

Other tattoos from the same region are not so easy to decipher. For example, two slightly diverging lines ran from high up on the forehead down over the full length of the nose. These tattoos were quite often the first ones to be placed upon pre-pubescent girls (6-10 years of age). Daniel S. Neuman, a doctor living in Nome, Alaska, wrote in 1917 that these tattoos (atngaghun) distinguished a woman "in after life from a man, on account of the similarity of [their] dress." Chukchi myths illustrate that these tattoos were the symbol par excellence of the woman herself. Tattoos also marked the thighs of young St. Lawrence Island women when they reached puberty. In Igloolik, Canada, some 2500 miles east of St. Lawrence Island, the tattooing of women's thighs ensured that the first thing a newborn infant saw would be something of beauty. They also made labor much easier for the woman.

MEDICINAL FUNCTION OF TATTOOS In the previous sections, the apotropaic aspect of tattoo has

been discussed, specifically as a remedy

Paramount to these concepts was the role of the preventive function. Circumpolar peoples were socialized and trained from their earliest days to build their bodies into pillars of strength through running, calisthenics, weightlifting, wading into frigid

Tattoo, as a curative agent, was often disorder-specific. Some maladies were cured with the application of small lines or marks on or near afflicted areas. Some examples from St. Lawrence Island are as follows:

In northwest Alaska, traditional practices of tattoo and ritually induced bleeding were often related and may have even overlapped to some extent. Around Bering Strait, shamans commonly performed bloodletting to relieve

aching or inflamed parts of the body. Nelson watched a shaman "lancing the

scalp of his little girl's head, the long, thin iron point of the instrument being

thrust twelve to fifteen times between

the scalp and skull." Similarly, the

Alaskan Aleuts performed bloodletting as remedies for numerous ailments attributed to "bad blood." On St.

Lawrence Island, bleeding was resorted to in cases of severe migraine headache or, as one St. Lawrence Islander has said, "to release anything with a high blood pressure...the [ancestors] kn[e]w that." The Chugach Eskimo treated sore eyes by bleeding at the root of the nose or at the temples. Then, the patient was made to swallow the blood, which affected the cure. TATTOO AS ACUPUNCTURE TOOL The shaman's prophetic role in medicinal practice was closely paralleled by that of the Chinese acupuncturist. Both were consulted to identify the causes of a disease, by differentiation of symptoms and signs, to provide suitable treatments. In acupuncture, pathogenic forces are thought to invade the human body from the exterior via the mouth, nose or body surfaces and the resultant diseases are called exogenous disease. In circumpolar cultures, and especially on St. Lawrence Island, the primary factor determining sickness was the intrusion of an evil spirit from outside the body into one of the souls of the afflicted individual. These types of malevolent actions of the spirit upon the body were traced to disordered behavior, possession, illness, and ultimately death. Consequently, and as a form of spiritual/medicinal practice, St. Lawrence Islanders tattooed specific joints. As mentioned earlier, joints served as the vehicular "highways" which evil entities traveled to enter the human body and injure it. Thus, joint-tattoos protected individuals by closing these pathways, since the substances utilized to produce tattoo pigment - urine, soot, seal-oil, and sometimes graphite - were the nexus of dynamic and apotropaic power, preventing an evil spirit from penetrating the human body. In both Chinese acupuncture theory and in St. Lawrence Island medicinal theory, it is believed that all ailments of the body, whether internal or external, are reflected at specific points either on the surface of the skin or just beneath it. In acupuncture, many of these points occur at the articulation of major joints and lie along specific pathways called meridians. Meridians connect the internal organs with specific points that are located either on or in the epidermis, often in close proximity to nerves and blood vessels. Evoking the Chinese acupuncturists' yin/yang cosmology, the body is in a perpetual state of dynamic equilibrium, oscillating between the poles of masculine and feminine, man and animal, sickness and health. Thus, relieving excess pressure at these points enables the body to regain its former state of homeostasis (harmony) within and outside of the body. As one can imagine, it is believed that there are many possible interrelationships and connections between organs, points, joints, and tattoos. Analysis of traditional St. Lawrence Island tattoo practices suggests that several tattooed areas on the body directly correspond to classical acupuncture points. In the recent past, these parallels were known to the St. Lawrence Islanders themselves. For example, one woman explained to me that one of the areas tattoos were placed upon coincides with the acupuncture point Yang Pai - utilized to remedy frontal headache and pain in the eye.

Of course, this type of remedy is quite ancient. The earliest known reference to acupuncture analgesia of this kind is in a legend about Hua To (A.D. 110-207), the first-known Chinese surgeon, who used acupuncture for headache. The Aleuts, as well as the ancient Chinese and St. Lawrence Islanders, utilized acupuncture in medicinal therapy. Acupuncture was resorted to in cases of headache, eye disorders, colic, and lumbago. Like the St. Lawrence Islanders, the Aleuts "tattoo-punctured" to relieve aching joints. The anthropologist Margaret Lantis observed that Aleut Atka Islanders, "moistened thread covered with gunpowder (probably soot in former times) sew[ing] through the pinched-up skin near an aching joint or across the back over the region of a pain."

|

||||

|

Ammassalik arm tattoo |

Kialegak mummy's |

Ammassalik breast tattoo, |

Ivory figurine from the Punuk culture displaying breast and arm tattoos |

|

|

"OETZI" AND THE PAZYRYK "CHIEF"

The precise location of these groupings attests to the exact location of major joint articulations in these areas. These groupings, coupled with the fact that 80% of the tattoo locations correspond to classical acupuncture points, combine to form the most common acupuncture convention for treating rheumatic illness. Thus, when X-ray analyses of Oetzi's body were performed, they revealed that he had considerable arthritis in the neck, lower back and right hip as well as a chronic arthritic condition in one of his little toes, probably due to severe frostbite. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that these results of degeneration, and the bluish tattoos associated with them, most certainly had the purpose of relieving pain in the joints - a folk remedy utilized in the Alps today. However, when these results are coupled with a reconstruction of a male mummy from the Altaian Pazyryk culture of the Russian steppes, excavated by archaeologist Sergei Rudenko in 1947-48, tattoo similarities become more compelling. This Pazyryk "chief" had dot-shaped tattoos on either side of the lumbar spine and on the right ankle, almost in the exact regions as that of the Iceman. Rudenko stated:

Not only did Pazyryk tattooing coincide with that of the Iceman in placement and function, it relates directly to the tattooing of St. Lawrence Island. First, the tattoo methods (pricking and sewing) practiced by the ancient Pazyryk tattooist were the same as those on St. Lawrence Island. Second, the raw materials are essentially the same: soot, fine needles, and sinew. Third, and although Pazyryk tattoos are not linear like Oetzi's, they occur in the dot-motif - exactly the same as on St. Lawrence Island. Fourth, the placement of the Pazyryk chief's tattoos are in the same general region as those applied during funeral ceremonies and first-kill observations on St. Lawrence Island: on the lower back or waist and at the ankle joint. When the therapeutic indications associated with Chinese acupuncture and St. Lawrence Island joint-tattoos are reviewed, then combined with comments on Aleut acupuncture, the Qilakitsoq mummies, Oetzi and the Pazyryk Chief, there is no doubt that the "tattoo-puncture" of the Aleuts, the ancient Greenlanders, the tattooing of the Iceman, the Pazyryk Chief, St. Lawrence Island pallbearers and first-kill participants provide striking parallels, the only variation being the numbers, aesthetics, and types of joint-tattoos. But do these apparent similarities relay more information than meets the eye? Obviously, all the marked evidence suggests that elements of Far-East Asian and surrounding regional cultures were likely sources of early influence upon early Bering Strait cultures, who, in turn, filtered these traits across the Arctic into Greenland. Therefore, it seems probable that each example of joint-tattooing may have been a sort of pan-human phenomenon, or better perhaps a pan-Eurasian one, encompassing the ages. Alternatively, this supposition could also suggest independent development of tattoo concepts and associative curative practices. CONCLUSION Regardless of the medical implications of tattoo and its origins, it is apparent that the practice of tattooing among Arctic peoples was quite homogenous. Considering the vast expanse of this culture area, the largest in the world, this may seem surprising. However, as a people unified by environment, language, custom, and belief, the distinction is quite clear: as tattoo became part of the skin, the body became a part of Arctic culture. Tattooing was a graphic image of social beliefs and values expressing the many ways in which Arctic peoples attempted to control their bodies, lives, and experiences. Tattoos provided a nexus between individual and communally defined forces that shaped perceptions of existence.

REFERENCES Anderson, H.D. and W.C. Eells. 1935. Alaska Natives: A Survey of Their Sociological and Educational Status. Stanford: University of Stanford Press. Apassingok, A., W. Walunga, and E. Tennant. 1985. Lore of St. Lawrence Island: Echoes of Our Eskimo Elders, Vol. I: Gambell. Unalakleet: Bering Strait School District. Barfield, L. 1994. "The Iceman Reviewed." Antiquity 68: 10-26. Birket-Smith, K. 1953. The Chugach Eskimo. Nationalmuseets Skrifter, Etnografisk Raekke 6. Copenhagen. Boas, F. 1901-07. The Eskimo of Baffin Land and Hudson Bay. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 15. New York. Bogojavlensky, S. 1969. Imaangmiut Eskimo Careers: Skinboats in Bering Strait. (Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation in Social Relations, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.) Bogoras, W. (also Bogoraz, V.G.). 1904-1909. The Chukchee. The Jesup North Pacific Expedition 7, Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History. New York. Chamisso, A. von. 1986 [1836]. A Voyage Around the World with the Romanzov Exploring Expedition in the Years 1815-1818 in the Brig Rurik. (H. Kratz, trans. and ed., reprinted 1986. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.) Chu, L.S.W., S.D.J. Yeh, and D.D. Wood. 1979. Acupuncture Manual: A Western Approach. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc. Coe, R.T. 1976. Sacred Circles: Two Thousand Years of North American Indian Art. Arts Council of Great Britain. London: Lund Humphries. Collins, H.B., Jr. 1929. "Prehistoric Art of the Alaskan Eskimo." Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 81(14): 1-52. Collins, H.B., Jr. 1930. "Notebook A." Unpublished Fieldnotes from the H.B. Collins Collection, Box 45, St. Lawrence Island. National Anthropological Archives, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution. Washington. Compilation. 1981. Essentials of Chinese Acupuncture. Oxford: Pergamon Press. Coughlan, A. 1994. "Alpine Iceman Was a Martyr to Arthritis." New Scientist 144 (1956): 10. Driscoll, B. 1987. "The Inuit Parka as an Artistic Tradition." Pp. 170-200 in The Spirit Sings: Artistic Traditions of Canada's First Peoples¸(D.F. Cameron, ed.). Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. Fitzhugh, W.W. and S.A. Kaplan. 1982. Inua: Spirit World of the Bering Sea Eskimo. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. Fortuine, R. 1985. "Lancets of Stone: Traditional Methods of Surgery Among the Alaska Natives." Arctic Anthropology 22(1): 23-45. Geist, O.W. 1927-34. Field Notes. On File, Alaska and Polar Regions Archives, University of Alaska, Fairbanks. Gilder, W.H. 1881. Schwatka's Search: Sledging in the Arctic in Quest of the Franklin Records. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Gordon, G.B. 1906. "Notes on the Western Eskimo." Transactions of the Department of Archaeology, Free Museum of Science and Art, 2(1): 69-101. Philadelphia. Hakluyt, R. 1907-1910 [1589]. Principal Navigations, Voyages, etc. of the English Nation. 8 vols. New York: E.P. Dutton. Harrington, R. 1981. The Inuit: Life As It Was. Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers Ltd. Hawkes, E.W. n.d. "Notes on the Asiatic Eskimo." Unpublished notes from the Bogoras Papers, Box 131-F-4, fldr. E. 1.1 New York City Public Library. Holm, G.F. 1914. "Ethnological Sketch of the Angmagsalik Eskimo." Meddelelser om Grønland 141 (1-2). Copenhagen. Hughes, C.C. 1959 "Translation of I.K. Voblov's 'Eskimo Ceremonies.'" Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska 7(2): 71-90. Hughes, C.C. 1960. An Eskimo Village in the Modern World. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Kapel, H., N. Kronmann, F. Mikkelsen, and E.L. Rosenlov. 1991. "Tattooing." Pp. 102-115 in The Greenland Mummies¸ (J.P.H. Hansen, J. Meldgaard, J. Nordqvist, eds.) Published for the Trustees of the British Museum. London: British Museum Publications. Kaplan, S.A. 1983. Spirit Keepers of the North: Eskimos of Western Alaska University Museum Publication. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Krutak, L. 1998. One Stitch at a Time: Ivalu and Sivuqaq Tattoo. (Unpublished Master's Thesis in Anthropology, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, Alaska.) Krutak, L. 1998. "St. Lawrence Island Yupik Tattoo: Body Modification and the Symbolic Articulation of Society." Chicago Anthropology Exchange 27: 54-82. Winter. Krutak, L. 1999. "Im Zeichen des Wals." Tätowier Magazin 5(39): 52-56. Krutak, L. 1999. "St. Lawrence Island Joint-Tattooing: Spiritual/Medicinal Functions and Intercontinental Possibilities." Études/Inuit/Studies 23(1-2): 229-252. Lantis, M. 1984. "Aleut." Pp. 161-184 in Arctic (Handbook of the North American Indians, vol. 5, D. Damas, ed.). Washington: Smithsonian Institution. Leighton, D. 1982. Field Notes (1940) of Dorothea Leighton and Alexander Leighton. On file in the archives of the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. Marsh, G.H. and W.S. Laughlin. 1956. "Human Anatomical Knowledge Among the Aleutian Islanders." Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 12(1): 38-78. McGhee, R. 1996. Ancient People of the Arctic. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. Nelson, E.W. 1899. The Eskimo About Bering Strait. Pp. 3-518 in 18th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology for the Years 1896-1897. Washington. Neuman, D.S. 1917. "Tattooing on St. Lawrence Island." The Eskimo, 1(11): 5. Nome. Petersen, R. 1996. "Body and Soul in Ancient Greenlandic Religion." Pp. 67-78 in Shamanism and Northern Ecology, (J. Pentikainen, ed.). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Reuters. 1998. "Iceman May Be First Patient of Treatment: Ancient Acupuncture." http://abcnews.go.com. Rudenko, S.I. 1949. "Tatuirovka aziatskikh eskimosov." Sovetskaia etnografiia 14: 149-154. Rudenko, S.I. 1970. Frozen Tombs of Siberia: The Pazyryk Burials of Iron Age Horsemen (M.W. Thompson, trans.). Berkeley: University of California Press. Scheper-Hughes, N. and M. Lock. 1987. "The Mindful Body: A Prolegomenon to Future Work in Medical Anthropology." Medical Anthropological Quarterly 1: 6-41. Schuster, C. 1951. "Joint-Marks: A Possible Index of Cultural Contact Between America, Oceania and the Far East." Koninklijk voor Tropen, Medeleling 44, Afdeling Culturale en Physiche Anthropologie 39: 3-51. Schuster, C. 1952. "V-Shaped Chest Markings: Distribution of a Design-Motive in and Around the Pacific." Anthropos 47: 99-118. Silook, P. 1940. "Life Story" and "Tattooe of Man." Unpublished Notes from the Dorothea C. Leighton Collection, Box 3, Folder 67 and 68, pp. 103-114, and p. 1-2, archives, University of Alaska, Fairbanks. Smith, G.S. and R. Zimmerman. 1975. "Tattooing Found on a 1600 Year Old Frozen, Mummified Body from St. Lawrence Island, Alaska." American Antiquity 40(4): 433-437. Spencer, R.F. 1959. The North Alaskan Eskimo: A Study in Ecology and Society. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 171. Washington. Spindler, K. 1994. The Man in the Ice: The Discovery of a 5,000-Year-Old Body Reveals the Secrets of the Stone Age (E. Osers, trans.). New York: Harmony Books. Stevenson, A. 1967. "Telltale Tattoos." North 14(6): 37-43. Taylor, J.G. 1984. "Historical Ethnography of the Labrador Coast." Pp. 508-521 in Arctic (Handbook of the North American Indians, vol. 5, D. Damas, ed.). Washington: Smithsonian Institution. Turner, L.M. 1887. Ethnological Catalogue of Ethnological Collections made by Lucien M. Turner in Ungava and Labrador, Hudson Bay Territory, June 24, 1882 to October 1, 1884. Prepared for the U.S. National Museum, May 1887. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Washington. Wardwell, A. 1986. Ancient Eskimo Ivories of the Bering Strait. New York: Hudson Hills Press. Weyer, E.M., Jr. 1932. The Eskimos: Their Environment and Folkways. New Haven: Yale University Press. |

||||

| Celeb Tattoos | Facts & Stats | Designs & Symbols | History | Culture | Links | Tattoo Galleries | Contact | ||||

|

Back to BERING SEA | Piercing in the Arctic | Vanishing Tattoo Home Other tattoo articles by Lars Krutak

Vanishing Tattoo Home :: Tribal Tattoos Worldwide :: Online Tattoo History Museum © 2011 VanishingTattoo.com |

||||

In the last century, however, tattoo on St. Lawrence Island, and more generally the Arctic, has been a dying, if not already dead, traditional practice. Disruptions to native society as a result of disease, missionization, and modernity paved the way for a relinquishing of ancient customs. For example, fewer than ten St. Lawrence Yupiget retain traditional tattoos: all date from the 1920's.

Alice Yavaseuk (age 96) was the last living tattoo artist and designer. However, she passed away unexpectedly in the fall of 2002. Thus, any student of tattooing must work with tidbits of information to unravel the vast complexities of a fast disappearing "magical art. "

In the last century, however, tattoo on St. Lawrence Island, and more generally the Arctic, has been a dying, if not already dead, traditional practice. Disruptions to native society as a result of disease, missionization, and modernity paved the way for a relinquishing of ancient customs. For example, fewer than ten St. Lawrence Yupiget retain traditional tattoos: all date from the 1920's.

Alice Yavaseuk (age 96) was the last living tattoo artist and designer. However, she passed away unexpectedly in the fall of 2002. Thus, any student of tattooing must work with tidbits of information to unravel the vast complexities of a fast disappearing "magical art. " HISTORY OF TATTOOING IN THE ARCTIC

HISTORY OF TATTOOING IN THE ARCTIC her reveal the cause. The parents were so indignant that they upbraided them and the girl in her shame fled from the village at night. As she ran past the fire she seized an ember and fled beyond the earth. Her brother pursued her and so the sparks fell from the torch [and] they became the stars in the sky. The brother pursued her but is able to overtake her except on rare occasions. These occasions are eclipses. When the moon wanes from sight the brother is supposed to be hiding for the approach of his sister."

her reveal the cause. The parents were so indignant that they upbraided them and the girl in her shame fled from the village at night. As she ran past the fire she seized an ember and fled beyond the earth. Her brother pursued her and so the sparks fell from the torch [and] they became the stars in the sky. The brother pursued her but is able to overtake her except on rare occasions. These occasions are eclipses. When the moon wanes from sight the brother is supposed to be hiding for the approach of his sister." "The wife has her face tattooed with lamp-black and is regarded as a matron in society. The method of tattooing is to pass a needle under the skin, and as soon as it is withdrawn its course is followed by a thin piece of pine stick dipped in oil and rubbed in the soot from the bottom of a kettle. The forehead is decorated with a letter V in double lines, the angle very acute, passing down between the eyes almost to the bridge of the nose, and sloping gracefully to the right and left before reaching the roots of the hair. Each cheek is adorned with an egg-shaped pattern, commencing near the wing of the nose and sloping upward toward the corner of the eye; these lines are also double. The most ornamented part, however, is the chin, which receives a gridiron pattern; the lines double from the edge of the lower lip, and reaching to the throat toward the corners of the mouth,

sloping outward to the angle of the lower jaw. This is all that is required by custom, but some of the belles do not stop here. Their hands,

arms, legs, feet, and in fact their whole bodies are covered with blue tracery that would throw Captain Constantinus completely in the shade."

"The wife has her face tattooed with lamp-black and is regarded as a matron in society. The method of tattooing is to pass a needle under the skin, and as soon as it is withdrawn its course is followed by a thin piece of pine stick dipped in oil and rubbed in the soot from the bottom of a kettle. The forehead is decorated with a letter V in double lines, the angle very acute, passing down between the eyes almost to the bridge of the nose, and sloping gracefully to the right and left before reaching the roots of the hair. Each cheek is adorned with an egg-shaped pattern, commencing near the wing of the nose and sloping upward toward the corner of the eye; these lines are also double. The most ornamented part, however, is the chin, which receives a gridiron pattern; the lines double from the edge of the lower lip, and reaching to the throat toward the corners of the mouth,

sloping outward to the angle of the lower jaw. This is all that is required by custom, but some of the belles do not stop here. Their hands,

arms, legs, feet, and in fact their whole bodies are covered with blue tracery that would throw Captain Constantinus completely in the shade." Whatever the outcome, the process in which the physical body became transformed and metamorphosed corresponded, in part,

to the nature of the tattooing pigments used, as well as to the social precepts circumscribing them. Among the Siberian Chukchi and

St. Lawrence Island Yupiget, lampblack was considered to be highly efficacious against evil as shamans utilized it in drawing magic circles around houses to ward off spirits. Graphite had similar powers as the Russian anthropologist Voblov stated in the 1930's, "[t]he stone spirit - graphite - 'guards' [humankind] from evil spirits and from the sickness brought by them." Urine, on the other hand, was an element that malevolent entities abhorred. Waldemar Bogoras, the eminent ethnographer of the Chukchi and Asiatic Eskimo, stated that urine, when poured over a spirit's head, froze upon contact immediately repelling the spiritual entity. In this connection, it is not surprising that several St. Lawrence Islanders told me that urine (tequq) was poured around the outside of houses to insure the same effect. In regards to tattooing, however, the ammonia content in urine probably helped cleanse and control the suppuration that resulted from the ritual.

Whatever the outcome, the process in which the physical body became transformed and metamorphosed corresponded, in part,

to the nature of the tattooing pigments used, as well as to the social precepts circumscribing them. Among the Siberian Chukchi and

St. Lawrence Island Yupiget, lampblack was considered to be highly efficacious against evil as shamans utilized it in drawing magic circles around houses to ward off spirits. Graphite had similar powers as the Russian anthropologist Voblov stated in the 1930's, "[t]he stone spirit - graphite - 'guards' [humankind] from evil spirits and from the sickness brought by them." Urine, on the other hand, was an element that malevolent entities abhorred. Waldemar Bogoras, the eminent ethnographer of the Chukchi and Asiatic Eskimo, stated that urine, when poured over a spirit's head, froze upon contact immediately repelling the spiritual entity. In this connection, it is not surprising that several St. Lawrence Islanders told me that urine (tequq) was poured around the outside of houses to insure the same effect. In regards to tattooing, however, the ammonia content in urine probably helped cleanse and control the suppuration that resulted from the ritual. Inuit (or Eskimos generally) and St. Lawrence Island Yupiget, in particular, like many other circumpolar peoples, regarded living bodies as inhabited by multiple souls, each soul residing in a particular joint. The anthropologist Robert Petersen has noted that the soul is the element that gives the body life processes, breath, warmth, feelings, and the ability to think and speak. Accordingly, the Eskimologist Edward Weyer stated in his tome, The Eskimos, that, "[a]ll disease is nothing but the loss of a soul; in every part of the human body there resides a little soul, and if part of the man's body is sick, it is because the little soul had abandoned that part, [namely, the joints]."

Inuit (or Eskimos generally) and St. Lawrence Island Yupiget, in particular, like many other circumpolar peoples, regarded living bodies as inhabited by multiple souls, each soul residing in a particular joint. The anthropologist Robert Petersen has noted that the soul is the element that gives the body life processes, breath, warmth, feelings, and the ability to think and speak. Accordingly, the Eskimologist Edward Weyer stated in his tome, The Eskimos, that, "[a]ll disease is nothing but the loss of a soul; in every part of the human body there resides a little soul, and if part of the man's body is sick, it is because the little soul had abandoned that part, [namely, the joints]." However, kakileq were also important to other aspects of the hunt. One of the old hunters in Gambell told me that "one reason for [the tattoos] is to hit the target, sometimes they don't [and] I think these are for that purpose, to hit the target." This is not surprising, since the anthropologist Robert Spencer remarked that tattoos on the North Slope of Alaska and other forms of adornment doubled as whaling charms, "serving to bring the whale closer to the boat, to make the animal more tractable and amenable to the harpooner." This type of sympathetic magic was also manifest in the stylized "whale-fluke" tattoos adorning the corners of men's mouths. Fittingly, these symbols were applied as part of first-kill observances among the Yupiget of St. Lawrence Island and Chukotka, as well as by other groups in the Arctic.

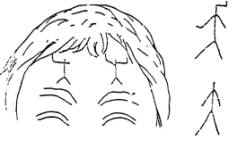

However, kakileq were also important to other aspects of the hunt. One of the old hunters in Gambell told me that "one reason for [the tattoos] is to hit the target, sometimes they don't [and] I think these are for that purpose, to hit the target." This is not surprising, since the anthropologist Robert Spencer remarked that tattoos on the North Slope of Alaska and other forms of adornment doubled as whaling charms, "serving to bring the whale closer to the boat, to make the animal more tractable and amenable to the harpooner." This type of sympathetic magic was also manifest in the stylized "whale-fluke" tattoos adorning the corners of men's mouths. Fittingly, these symbols were applied as part of first-kill observances among the Yupiget of St. Lawrence Island and Chukotka, as well as by other groups in the Arctic. The tattooing process involved iconographic manifestation of the "other side," acknowledgment of the manifestation's power, and harnessing that power within the corporeal envelope of human skin. On St. Lawrence Island, men and women tattooed anthropomorphic spirit-helpers onto their foreheads and limbs. These stick-like

figures, more appropriately named "guardians" or "assistants," protected individuals from evil spirits, disasters at sea, unknown areas where one traveled, strangers, and even in the case of new mothers, the loss of their children. In Chukotka, murderers inscribed these types of markings onto their shoulders in hopes of appropriating the soul of their victim, thus transforming it into an "assistant," or even into a part of himself.

The tattooing process involved iconographic manifestation of the "other side," acknowledgment of the manifestation's power, and harnessing that power within the corporeal envelope of human skin. On St. Lawrence Island, men and women tattooed anthropomorphic spirit-helpers onto their foreheads and limbs. These stick-like

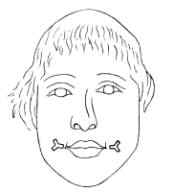

figures, more appropriately named "guardians" or "assistants," protected individuals from evil spirits, disasters at sea, unknown areas where one traveled, strangers, and even in the case of new mothers, the loss of their children. In Chukotka, murderers inscribed these types of markings onto their shoulders in hopes of appropriating the soul of their victim, thus transforming it into an "assistant," or even into a part of himself. Apart from these concepts, there seems to have been some relationship between labrets and tattoos, at least in the Bering Strait region. Adelbert von Chamisso, a naturalist with Kotzebue's expedition

of 1815-1818, noted that labrets were rare among St. Lawrence Island men and often replaced by a tattooed spot. Edward W. Nelson, a naturalist

working for the U.S. Army Signal Service in the late 19th century, also suggested that these circular tattoos were a relic of wearing a lip-plug or

labret. Bogoras believed that this was probably true, though their position did not quite "correspond to the usual position of the labret. These marks are now intended only as charms against the spirits." Dewey Anderson and Walter Eells, two sociologists from Stanford University who visited St. Lawrence Island in the 1930's, recorded that "a small circle on the lower lip under the corners of the mouth [was tattooed] to prevent a man who has repeatedly fallen into the sea from drowning." Similarly, a Diomede Islander from Bering Strait was seen at the turn of the century with a mark tattooed at each corner of the mouth. He explained it as a preventive prescribed by his mother against the fate that had befallen his father - death by drowning.

Apart from these concepts, there seems to have been some relationship between labrets and tattoos, at least in the Bering Strait region. Adelbert von Chamisso, a naturalist with Kotzebue's expedition

of 1815-1818, noted that labrets were rare among St. Lawrence Island men and often replaced by a tattooed spot. Edward W. Nelson, a naturalist

working for the U.S. Army Signal Service in the late 19th century, also suggested that these circular tattoos were a relic of wearing a lip-plug or

labret. Bogoras believed that this was probably true, though their position did not quite "correspond to the usual position of the labret. These marks are now intended only as charms against the spirits." Dewey Anderson and Walter Eells, two sociologists from Stanford University who visited St. Lawrence Island in the 1930's, recorded that "a small circle on the lower lip under the corners of the mouth [was tattooed] to prevent a man who has repeatedly fallen into the sea from drowning." Similarly, a Diomede Islander from Bering Strait was seen at the turn of the century with a mark tattooed at each corner of the mouth. He explained it as a preventive prescribed by his mother against the fate that had befallen his father - death by drowning. Adopting the anatomical characteristic of the walrus (tusks) may have ideologically captured the essence of its aggressive behavior or transformed the hunter into this creature. This would not be surprising since the concept of transformation - men into animals, animals into men, and animals into animals - permeates all aspects of life in the Bering Strait and is expressed on all kinds of objects. No doubt this deceptive "tattoo foil" subverted the attention of the foe and safeguarded the hunter from malicious attack.

Adopting the anatomical characteristic of the walrus (tusks) may have ideologically captured the essence of its aggressive behavior or transformed the hunter into this creature. This would not be surprising since the concept of transformation - men into animals, animals into men, and animals into animals - permeates all aspects of life in the Bering Strait and is expressed on all kinds of objects. No doubt this deceptive "tattoo foil" subverted the attention of the foe and safeguarded the hunter from malicious attack. There seems to have been no widely distributed tattoo design among Eskimo women, although chin stripes (tamlughun) were more commonly found than any other. Chin stripes served multiple purposes in social contexts. Most notably, they were tattooed on the chin as part of the ritual of social maturity, a signal to men that a woman had reached puberty. Chin stripes also served to protect women during enemy raids. Traditionally,

fighting among the Siberians and St. Lawrence Islanders took place in close quarters, namely in various forms of semi-subterranean

dwellings called nenglu. Raiding parties usually attacked in the early morning hours,

at or before first light, hoping to catch their enemies while asleep. Women, valued as important "commodities" during these times, were highly prized for their many abilities. Not being distinguishable from the men by their clothing in the dim light of the nenglu, their chin stripes made them more recognizable as females and their lives would be spared. Once captured, however, they were bartered off as slaves.

There seems to have been no widely distributed tattoo design among Eskimo women, although chin stripes (tamlughun) were more commonly found than any other. Chin stripes served multiple purposes in social contexts. Most notably, they were tattooed on the chin as part of the ritual of social maturity, a signal to men that a woman had reached puberty. Chin stripes also served to protect women during enemy raids. Traditionally,

fighting among the Siberians and St. Lawrence Islanders took place in close quarters, namely in various forms of semi-subterranean

dwellings called nenglu. Raiding parties usually attacked in the early morning hours,

at or before first light, hoping to catch their enemies while asleep. Women, valued as important "commodities" during these times, were highly prized for their many abilities. Not being distinguishable from the men by their clothing in the dim light of the nenglu, their chin stripes made them more recognizable as females and their lives would be spared. Once captured, however, they were bartered off as slaves. A full set of lines was not only a powerful physical statement of the ability to endure great pain but also an attestation to a woman's powers of "animal" attraction. In the St. Lawrence and Chaplino Yupik area of the early 20th century, women painted and tattooed their faces in ritual ceremonies in order to imitate, venerate, honor, and/or attract those animals that "will bring good fortune" to the family. Waldemar Bogoras noted, "[i]t is a mistake to think that women are weaker then men in hunting-pursuits," since as a man wanders in vain about the wilderness, searching, women "that sit by the lamp are really string, for they know how to call the game to the shore."

A full set of lines was not only a powerful physical statement of the ability to endure great pain but also an attestation to a woman's powers of "animal" attraction. In the St. Lawrence and Chaplino Yupik area of the early 20th century, women painted and tattooed their faces in ritual ceremonies in order to imitate, venerate, honor, and/or attract those animals that "will bring good fortune" to the family. Waldemar Bogoras noted, "[i]t is a mistake to think that women are weaker then men in hunting-pursuits," since as a man wanders in vain about the wilderness, searching, women "that sit by the lamp are really string, for they know how to call the game to the shore." Slightly sloping parallel lines, usually consisting of three tightly grouped bands on the face, were also tattooed on women. Bogoras mentioned that childless Chukchi women "tattoo on both cheeks three equidistant lines running all the way around. This is considered one of the charms against sterility." There is a similar belief related in the story of Ayngaangaawen, a woman from the extinct St. Lawrence

Island village of Kookoolok. Ayngaangaawen refused to get her tattoo marks. She could not bear healthy children, and as a result, they all died as infants. Supposedly, "when she got some marks she had children" and they lived into adulthood.

Slightly sloping parallel lines, usually consisting of three tightly grouped bands on the face, were also tattooed on women. Bogoras mentioned that childless Chukchi women "tattoo on both cheeks three equidistant lines running all the way around. This is considered one of the charms against sterility." There is a similar belief related in the story of Ayngaangaawen, a woman from the extinct St. Lawrence

Island village of Kookoolok. Ayngaangaawen refused to get her tattoo marks. She could not bear healthy children, and as a result, they all died as infants. Supposedly, "when she got some marks she had children" and they lived into adulthood. Intricate scrollwork found on the cheeks (qilak), and tattoos on the

arms of women (iqalleq), possibly form elements of a genealogical puzzle. Most women of St. Lawrence Island say these tattoos are

simply "make-up," beautifying their bodies. Dr. Neuman verified that this was the case in 1917, but he also believed that

"each tribe adhered to their own design but with a slight modification for their

own individual members. The designs on the hands and arms often combined tribal and family designs and formed, so to speak, a family tree." On the arms of one my female informants, rows of fluke tails

extend from her wrists to the middle of her forearms. These symbols represent her clan (Aymaramket), an honored lineage of great whale

hunters.

Intricate scrollwork found on the cheeks (qilak), and tattoos on the

arms of women (iqalleq), possibly form elements of a genealogical puzzle. Most women of St. Lawrence Island say these tattoos are

simply "make-up," beautifying their bodies. Dr. Neuman verified that this was the case in 1917, but he also believed that

"each tribe adhered to their own design but with a slight modification for their

own individual members. The designs on the hands and arms often combined tribal and family designs and formed, so to speak, a family tree." On the arms of one my female informants, rows of fluke tails

extend from her wrists to the middle of her forearms. These symbols represent her clan (Aymaramket), an honored lineage of great whale

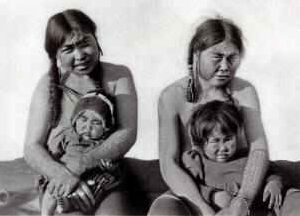

hunters. From the preceding remarks, it seems as though a woman's tattoo designs were individualistic. However, tattoos found on the back of the hand (igaq) were not. These motifs seem to mark the identities of individuals belonging to a cohort. For example, the women that retain igaq (two are shown below) have identical tattoo patterns and it is these women that were the last age group to be tattooed on St. Lawrence Island ca. 1920.

From the preceding remarks, it seems as though a woman's tattoo designs were individualistic. However, tattoos found on the back of the hand (igaq) were not. These motifs seem to mark the identities of individuals belonging to a cohort. For example, the women that retain igaq (two are shown below) have identical tattoo patterns and it is these women that were the last age group to be tattooed on St. Lawrence Island ca. 1920. against supernatural possession. In the light of indigenous theory of disease

causation - evil spirits - it is not surprising that tattoo was considered

as a form of medicine against a variety of ills. This medicine was believed to act as a preventive or as a curative one.

against supernatural possession. In the light of indigenous theory of disease

causation - evil spirits - it is not surprising that tattoo was considered

as a form of medicine against a variety of ills. This medicine was believed to act as a preventive or as a curative one. waters, etc. Only when a biological disorder rose to life threatening levels, where "preventive" medicinal practice had failed the cure, it then became the responsibility of the shaman to summon

his or her spiritual powers to safeguard

and restore health. Disorders, as well as other inexplicable misfortunes, were attributed to supernatural agency and were believed to be remediable through the use of tattoo. Oftentimes, these types of medicinal tattoos were applied by shamans, though not always.

waters, etc. Only when a biological disorder rose to life threatening levels, where "preventive" medicinal practice had failed the cure, it then became the responsibility of the shaman to summon

his or her spiritual powers to safeguard

and restore health. Disorders, as well as other inexplicable misfortunes, were attributed to supernatural agency and were believed to be remediable through the use of tattoo. Oftentimes, these types of medicinal tattoos were applied by shamans, though not always. It is plausible that the release of blood functioned to appease various ills and spiritual manifestations. For instance, several St. Lawrence Islanders explained to me the importance of licking the blood that was released during tattoo "operations." The female tattoo artist, who performed the skin-stitching, licked the blood sometimes, "because that helps, to a, for them to have a good sight." Evidently, bad blood released from the tattoo rite acted as a supplementary healing agent remedying specific ailments. Reliance on this expedient might seem to have grown out of the impression that the expulsion of the evil spirit would be facilitated through the escaping stream of blood. Thus, by harnessing blood orally, and/or neutralizing it with saliva, the tattoo artist transformed it into a sanctifying substance.

It is plausible that the release of blood functioned to appease various ills and spiritual manifestations. For instance, several St. Lawrence Islanders explained to me the importance of licking the blood that was released during tattoo "operations." The female tattoo artist, who performed the skin-stitching, licked the blood sometimes, "because that helps, to a, for them to have a good sight." Evidently, bad blood released from the tattoo rite acted as a supplementary healing agent remedying specific ailments. Reliance on this expedient might seem to have grown out of the impression that the expulsion of the evil spirit would be facilitated through the escaping stream of blood. Thus, by harnessing blood orally, and/or neutralizing it with saliva, the tattoo artist transformed it into a sanctifying substance. "Grandparents, when they were pricking that [point when they] hurt from headache, when [they] thought that [the] eyes are bothering you...they use, a, acupuncture."

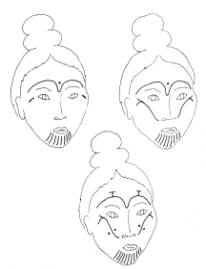

"Grandparents, when they were pricking that [point when they] hurt from headache, when [they] thought that [the] eyes are bothering you...they use, a, acupuncture." Apparently, the use of this potent medical technology was not confined to the North Pacific Rim, since it also reached Greenland in the distant past. Radiocarbon dated to the 15th century

A.D., the mummies of Qilakitsoq have revealed that a conscious, exacting attempt was made to place dot-motif tattoos at important facial loci. Being that these dot-motif tattoos are suggestive of acupuncture points,

and coupled with the fact that each actually designates a classical acupuncture point, cultural affinity must be suggested. Besides, Danish ethnologist Gustav Holm reported in 1914 that East Greenlanders "now and then...resort to tattooing in cases of sickness." Although we are not entirely sure if Holm was specifically referring to "tattoo-puncture" in his statement, two intriguing 1500 year old "doll-heads" excavated from St. Lawrence Island illustrate ancient continuity spanning thousand of miles and hundreds of years.

Apparently, the use of this potent medical technology was not confined to the North Pacific Rim, since it also reached Greenland in the distant past. Radiocarbon dated to the 15th century

A.D., the mummies of Qilakitsoq have revealed that a conscious, exacting attempt was made to place dot-motif tattoos at important facial loci. Being that these dot-motif tattoos are suggestive of acupuncture points,

and coupled with the fact that each actually designates a classical acupuncture point, cultural affinity must be suggested. Besides, Danish ethnologist Gustav Holm reported in 1914 that East Greenlanders "now and then...resort to tattooing in cases of sickness." Although we are not entirely sure if Holm was specifically referring to "tattoo-puncture" in his statement, two intriguing 1500 year old "doll-heads" excavated from St. Lawrence Island illustrate ancient continuity spanning thousand of miles and hundreds of years.

In the early 1970's beach erosion exposed the heavily tattooed, mummified body of an

Old Bering Sea/Okvik woman radio-carbon dated to 1600 years ago corrected at A.D. 390-370 (±90 years) at Cape Kialegak, St. Lawrence Island. Her forearm

tattoos were very reminiscent of those seen in late 19th century photographs of East Greenlanders at Ammassalik. Other

Ammassalimniut women displayed breast and arm tattoos similar to engraved

female ivory figurines from the Punuk culture of St. Lawrence Island, suggesting that these practices persisted remarkably over the centuries. Therefore, it seems that

the related styles of unilateral tattooing of the breast and the bilateral marking of the upper arms stress cultural unity for the Eskimo area as a whole and, more specifically,

of material culture from Greenland to the ancient cultures of St. Lawrence Island.

In the early 1970's beach erosion exposed the heavily tattooed, mummified body of an

Old Bering Sea/Okvik woman radio-carbon dated to 1600 years ago corrected at A.D. 390-370 (±90 years) at Cape Kialegak, St. Lawrence Island. Her forearm

tattoos were very reminiscent of those seen in late 19th century photographs of East Greenlanders at Ammassalik. Other

Ammassalimniut women displayed breast and arm tattoos similar to engraved

female ivory figurines from the Punuk culture of St. Lawrence Island, suggesting that these practices persisted remarkably over the centuries. Therefore, it seems that

the related styles of unilateral tattooing of the breast and the bilateral marking of the upper arms stress cultural unity for the Eskimo area as a whole and, more specifically,

of material culture from Greenland to the ancient cultures of St. Lawrence Island.

In 1991, an alpine "Iceman" some 5500 years old was discovered in the Tyrolean Alps. The Iceman "Oetzi" is the oldest known human to have medicinal tattoos preserved upon his

mummified skin. His tattoos, according to Conrad Spindler, were located as follows:

In 1991, an alpine "Iceman" some 5500 years old was discovered in the Tyrolean Alps. The Iceman "Oetzi" is the oldest known human to have medicinal tattoos preserved upon his

mummified skin. His tattoos, according to Conrad Spindler, were located as follows: "Tattooing could be done either by stitching or by pricking in order to introduce a

black colouring substance, probably soot, under the skin. The method of pricking is

more likely than sewing, although the Altaians of this time had very fine needles and thread with which to have executed this..."

"Tattooing could be done either by stitching or by pricking in order to introduce a

black colouring substance, probably soot, under the skin. The method of pricking is

more likely than sewing, although the Altaians of this time had very fine needles and thread with which to have executed this..."