| Celeb Tattoos | Facts & Stats | Designs & Symbols | History | Culture | Links | Tattoo Galleries | Contact | ||

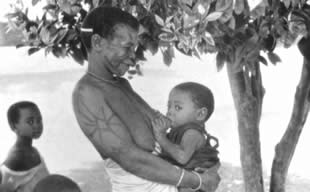

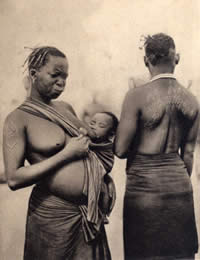

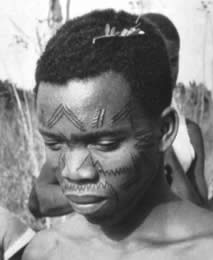

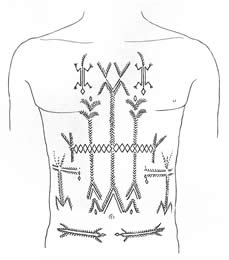

Dinembo: Tribal Tattoos of the Makonde© 2006 by Lars Krutak Among the Bantu-speaking Makonde, tattoos were and continue to be far more elaborate than those of other indigenous peoples living in Mozambique. The resonance of tattooing tradition here can partly be attributed to the landscape in which the Makonde inhabit, a place characterized by relatively inaccessible high plateaus that deterred European and Western contact until the turn of the 20th century; and also to Makonde cosmology and myth which to this day praises the deeds, knowledge, and superior physical attributes of the "great" ancestors of the past, especially tattooed women who became god-like after death. Traditionally, Makonde tattoos were considered as regional indicators and each tribe preferred specific motifs that were laid down in a variety of set patterns. The face and other parts of the body contained chevrons, angles, zigzag and straight lines with an occasional circle, diamond, dot, or animal figure. Today these patterns have remained largely intact since each generation of Makonde tattooists has only slightly modified their oeuvre, obeying traditional principles that guide their work. To date, the only major innovation within tattooing tradition is the technology itself; and the old triangular tattoo knife has been replaced by a finer razor-bladed model that cuts the skin more evenly and accurately. MAKONDE TATTOOISTS and THEIR CLIENTSGenerally speaking, Makonde men tattoo boys and women the girls although overlap between the sexes does occur to some degree. Makonde tattoo artists are "professionals" who learn their skills usually from their parents or from other family members. The general Makonde term for tattoo is dinembo ("design" or "decoration") and the tattooing process usually requires three or more sessions with the mpundi wa dinembo ("tattoo design artist") to produce the desired result. After the cuts have been made with the traditional tattoo implements (chipopo), vegetable carbon is rubbed into the incisions producing a dark blue color. Tattoo clients, who pay a nominal fee, are held down in a spread-eagle fashion. Just before the tattoo artist begins to ply her tool, she mentally records which designs she will mark. Moving carefully over the skin, she cuts then presses the pigment to the wound until she has finished, leaving the client to dry her wounds in the afternoon sun. After several days, the face is washed and the black lines created by the pigment now begin to show more clearly. Six months later, the entire process is repeated again, but with each successive tattoo layer, a greater relief pattern appears. Finally, a third operation is made which completes the work. Some girls lose their courage when it is time for the second or third operation and they never complete the painful tattooing. Those who run away are ridiculed and even threatened by the woman who acts as their "godmother" during the dinembo rite, because for the Makonde the tattoo ritual is a sign of courage and "To Show I am a Makonde."

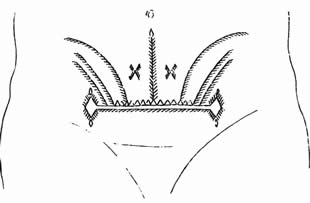

TATTOO MOTIFSCommon decorative motifs such as spiders (lidangadanga), crocodiles (nantchiwanuwe), and even yucca root bundles (nkaña) may have had magical associations in the past. And today Makonde women continue to believe that the tattoos placed on their abdomen (mankani) and inner thighs (nchika) have the supernatural power to attract a husband. Of course, the motifs used to decorate these areas, usually palm tress or their fruit (nadi) and especially lizards (magwañula), are believed to enhance fertility. However, the Makonde practice of tattooing the navel and pubic areas was perhaps related to the long-standing tradition of prophylactic "magic" aimed at warding off penetration or possession by evil forces that targeted vulnerable body passageways, namely the natural openings of the body. Armitage (1924) cites several instances of navel scarification among Bantu-speaking Gonja and Dagomba women in Ghana "put on to ward off or prevent sickness" while the anthropologists Nevadomsky and Aisien (1995) described five tattoos stemming from the navel ("the center of life") among the Bini women of Benin. Not surprisingly, the Bini prepared their tattoo pigments from leaves and lampblack, and at funerals mourners "rub a line of lamp-black on their foreheads to scare away the spirit of the deceased who tries to drag his relatives with him to the world of the dead." SPIRITUAL LIFE of the MAKONDEThe Makonde adhered to a cosmology dominated by a powerful impersonal force (ntela), the propitiation of ancestral spirits (mahoka) who were sometimes good or evil, and a concept of pervasive bush spirits (nnandenga) and sorcerers who were a form of malevolence. The spirits of ancestors were often called upon to send cures for sickness, and to ensure success in the harvest or in hunting. Mahoka also served as intermediaries between the living and Nnungu, a powerful deity who was invoked during major droughts when the Makonde collectively prayed for rain. On the malevolent order, spirits of the dead called mapiko only terrorized women and the non-initiated, while sorcerers created invisible slaves from humans called lindandosa that were sent to the agricultural fields to work their evil magic. Because excessive fear of death pervaded Makonde belief, its stigma had to be controlled or pre-empted because it threatened the basic assumptions of cosmic order on which society rested. Thus, every woman understood that her participation in society could provoke the negative intervention of powerful spiritual forces made manifest as mahoka, nnandenga, lindandosa, or mapiko who were the ultimate guarantors of social, physical, and economic survival. In this sense, Makonde tattoo arts were an important tool for fostering productive interaction between human beings and spirits, because it is clear that the designs repeatedly tattooed on women helped to secure their commitment to the potencies that bring forth life and to the socialization process of initiation itself. Tattoos also constructed a common visual language through which these relationships could be tangibly expressed and mediated to provide the individual wearer with a means to control her surrounding world. Similarly, Makonde sculpture and more utilitarian objects like gourds (situmba) and water pots, which embody feminine and reproductive qualities, symbolically reinforced this commitment to order and stability because they were often decorated with tattoo designs. As "ancestral implements" used for carrying water, beer, honey, and seeds for planting, gourds were considered to be female symbols par excellence. And like the tattooed bodies of Makonde women, they acted as conduits through which symbolic meaning poured; meaning that connected the human, spiritual, and ancestral communities of the Makonde of Mozambique. LITERATUREArmitage, C.H. (1924) |

||

Other tattoo articles by Lars Krutak

© 2006 Lars Krutak |

||

| Celeb Tattoos | Facts & Stats | Designs & Symbols | History | Culture | Links | Tattoo Galleries | Contact |