MANY STITCHES FOR LIFE:

THE ANTIQUITY OF THREAD AND NEEDLE TATTOOING

| |

|

| |

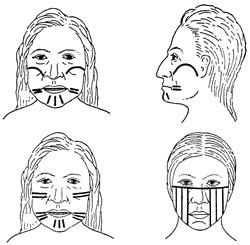

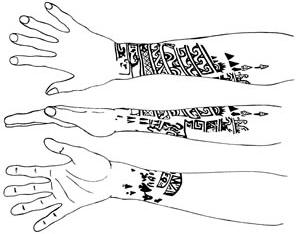

Facial and body tattoos of the Thompson River Salish (Nlaka'pamux), British Columbia, Canada, 1910. |

Article © 2008 Lars Krutak

For thousands of years, indigenous

peoples around the world marked their bodies

with skin-stitched tattoos. This painful

form of body art was not just the latest

fashion, it was a visual language that

exposed an individual's desires and fears as

well as ancient cultural values and

ancestral ties that were written on the

body.

Although some of these tattoos did hold an iconic allure, others were

believed to have had magical power and purpose. For example, three

vertical bands tattooed on the cheeks of St. Lawrence Island, Alaska

women were thought to induce fertility, while other configurations of

markings were believed to protect them from unseen enemies or illnesses

borne from evil spirits. Still more designs were thought to attract prey

animals and even men. The Thompson River Salish (Nlaka'pamux) of Canada

also tattooed for ornamental purposes, but they sometimes inscribed

their bodies with thread and needle to show courage, to acquire

strength, to or to display enduring fidelity and love in marriage. The

Nlaka'pamux also marked their bodies to ward off death and sickness or

to acquire a guardian spirit.

Sadly, however, skin-stitched tattooing has largely disappeared in

the world along with its practitioners. In Canada, only one Inuit woman

living on King William Island retains her elaborate facial and body

tattoos. And to date, just a handful of Siberian Yupik and Chukchi women

in Siberia continue to wear similar indelible markings.

Tattooing in the Arctic

St. Lawrence Island

Yupik woman with facial tattoos.

Photograph © 1997 Lars Krutak.

|

|

By far skin-stitched

tattoos were most popular among the

indigenous peoples of the Arctic. In

fact, this style of tattooing was

practiced for over 2,000 years and

was most common among women. As a

general rule, expert tattoo artists

were respected elderly women. Their

extensive training as skin

seamstresses (parkas, pants, boots,

hide boat covers, etc.) facilitated

the need for precision when

stitching the human skin with

tattoos.

Tattoo designs were usually made

freehand but in some instances a

rough outline was first sketched

upon the face, arms, hands, and

other body parts that were to be

tattooed. On St. Lawrence Island,

the tattoo pigment was made from the

soot (aallneq) of seal oil lamps

which was taken from the bottom of

tea kettles or similar containers

used to boil meat or other foods.

The soot was mixed with urine (tequq),

often that of an old woman, and

sometimes graphite (tagneghli) or

seal oil was added. Next, a sinew (ivalu)

thread from a reindeer was drawn

through the eye of a needle and

dipped into the coloring substance.

This thread was then inserted just

under the skin for a distance of

about a 1/32 of an inch and after

several stitches tiny dots began to

form lines and other desired motifs.

Tattooing needles were traditionally

made from slivers of bone, but as

time passed St. Lawrence Islanders (Sivuqaghhmiit)

began using steel needles for

skin-stitching. According to one of

the last tattooed elders, a very

small bag of seal intestine was used

to hold the tattoo needle: "they

don't use this needle for anything

else, they just keep it in there and

nobody else is supposed to touch it

except the one who used it." Of

course, when anyone was injured

either accidentally or willfully by

the needle, it was not used again

until the wound had healed. If

sickness resulted on account of such

an injury or if death occurred, the

needle was taken with the body of

the dead or it was destroyed.

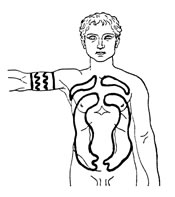

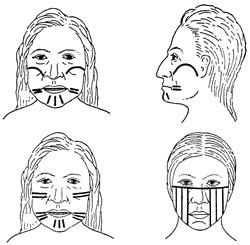

Although ornamental and family

designs were applied to most parts

of the body (e.g., face, arms, torso

and hands), medicinal tattoos akin

to acupuncture were placed on

particular joints. Of course, the

Sivuqaghhmiit were not the only

indigenous people to sport such

markings. The 5,000-year-old Iceman

wore similar medicinal tattoos at

rheumatic joints as did members of

the nomadic Pazyryk people who ruled

the Siberian steppes some 2,500

years ago. The Unangan and Alutiiq

of the Aleutian Islands also

utilized this medicinal treatment. |

|

Flora Imergan (Elqiilaq), who died in 2000, was one of the last completely tattooed women of St. Lawrence Island, Alaska. All of Elqillaq's facial tattoos date from the 1920s, and consist of fertility markings and other motifs near the ear called qilak or "heavens."

Photograph © 1997 Lars Krutak.

|

|

Siberian Yupik woman "stitching the skin" at Indian Point, Chukotka, 1901. Photograph by Waldemar Bogoras.

Siberian and St. Lawrence Island

Yupik girls became women after

receiving their first skin-stitched

tattoos at the onset of puberty.

Women who could not endure the

painful skin-stitching were

ridiculed by their peers, and

sometimes they had difficulty in

finding a husband. Today, only a

handful of Siberian Yupik and Chukchi women possess these

markings. Sadly, the tradition is

now extinct on St. Lawrence Island. |

|

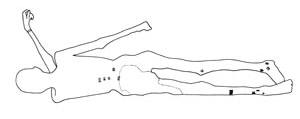

The 5,000-year-old Iceman. Small lines of therapeutic tattooing have been found on his rheumatic joints, and 80% of the Iceman's tattoos correspond to actual acupuncture points. Interestingly, archaeological evidence indicates that the earliest form of tattooing was not medicinal but rather cosmetic. And around 8,000 years ago, at least one man of the Chile was tattooed with what looks like a small mustache on his upper lip. It is believed that this tattoo was pricked-in rather than sewn.

Tattooed Unangan woman of Unalaska

Island, Alaska, 1778. Drawing by

John Webber.

Although the peoples of the Aleutian

Islands used medicinal tattooing for

complaints in their joints, the

Russian priest Veniaminov wrote

around 1830 that Unangan women from

Unalaska Island (Alaska) wore

skin-stitched tattoos across their

faces and bodies because, "the

pretty ones and also the daughters

of famous and rich ancestors and

fathers, endeavored in their

tattooings to show the

accomplishments of their

progenitors, as for instance, how

many enemies, or powerful animals,

that ancestor killed."

|

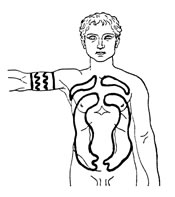

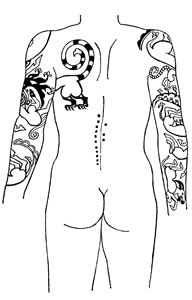

Above:

Pazyryk chief with medicinal

dot-tattooing & elaborate zoomorphic body tattooing, 500 B.C. |

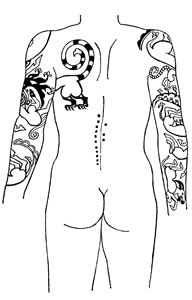

Chimú

The Chimú of Pre-Columbian Peru applied

tattoo pigments with various types of

needles (fishbone, parrot quill, spiny

conch) which have been found in mummy

burials. The technical application of

tattooing was a form of skin-stitching, and

it has been suggested that women were the

primary tattoo artists.

Paleopathological studies of Chimú mummies

(1100-1470 A.D.) indicate that the practice

of tattooing was quite common among both

males and females. In some coastal

settlements, it has been estimated that at

least thirty percent of the population may

have been tattooed.

Interestingly, the Chimú seemed to have used

the juices of the genipap (genipa americana

L.) as tattoo pigment. Juices of the green,

immature fruits of the genipap have and

continue to be used as black body paint and

tattoo pigment by historic and contemporary

indigenes of South America. Among some

groups, the coloring substance was highly

esteemed because it was believed to repel

incorporeal spirits. This was especially

true of the headhunting Jívaro and Mundurucú

who painted themselves and their

trophy

heads with genipap to protect the victor

from the spirit of the deceased.

|

|

|

Chimú mummies with naturalistic and

geometric tattooing, 1200 A.D.

Drawing courtesy of Dr. Marvin

Allison.

Hidden in shifting sands along the

coastal valleys of Peru, mummies of

the Chimú culture have been

discovered bearing intricate tattoos

of animals, weapons, landscape

features, and anthropomorphic

deities. Similar designs were

engraved into wood, silver, and

hammered gold burial gloves. Tattoos

of the sacred dead perhaps served as

magical mediators between this world

and the next by carrying the body

into the afterlife. |

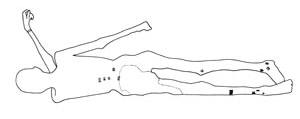

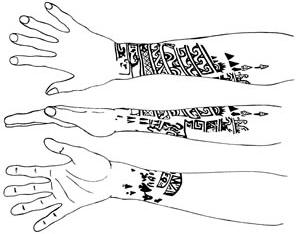

According to

pathologist Dr. Marvin J.

Allison, the leg tattoos of this

recently excavated Tiwanaku

mummy (1000 A.D.) from Peru were

stitched-in with needle and

thread. Photograph © 2005 Marvin

J. Allison.

Tiwanaku culture mummy with skin-stitched avian tattoos on the forearm and other designs, possibly spiders, on the knuckles, 1000 A.D. Photograph © 2005 Marvin J. Allison.

|

Above:

Chimú burial gloves of hammered gold

with tattoo designs, 1200-1300 A.D.

Collection of the

Museo Oro del Perú. |

Many Stitches for Life

Skin-stitched tattoos firmly anchored

indigenous values on the skin by creating a

visual mosaic rooted in traditional

practice. These tattoos not only satisfied

the need for display and personal

accomplishment; they also embodied religious

beliefs about the relationships between

humans, animals, spirits, and the ancestors

who controlled human destiny and the

surrounding world. Thus, as a system of

tools and techniques by which indigenous

people used to relate to their environment,

community, and culture, skin-stitched

tattooing expressed the many ways in which

indigenous people attempted to control their

bodies, lives, and experiences.

Museum photo gallery of these images may

be seen here.

Literature

Allison, J. Marvin, Lawrence Lindberg,

Calogero Santoro, and Guillermo Foracci.

(1981). "Tatuajes Y Pintura Corporal de Los

Indigenas Precolumbinos de Peru Y Chile."

Chungara 7: 218-225.

Karsten, Rafael. (1926). Civilization of the South American Indians:

With Special Reference to Magic and Religion. London: Kegan Paul.

Rudenko, Sergei I. (1970). Frozen Tombs of Siberia; The Pazyryk

Burials of Iron Age Horsemen. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Teit, James A. (1930). "Tattooing and Face and Body Painting of the

Thompson Indians, British Columbia." Pp. 397-439 in 45th Annual Report

of the Bureau of American Ethnology. Washington: U.S. Government

Printing Office.

Veniaminov, Ivan E.P. (comp.). (1840). Zapiski ob ostrovakh

Unalashkinskago otdiela [Notes on the Islands of the Unalaska District].

3 vols. in 2. St. Petersburg: Russian-American Company. |