India: Land of Eternal Ink

Article © 2009 Lars Krutak

Gujarat

Not surprisingly, several tribes in Gujarat

like the agrarian Mer believe that tattoos,

not prosperity or wealth, are the only

substantive things that accompany them into

the afterlife. A Mer proverb relates: "We

may be deprived of all things of this world,

but nobody has the power to remove the

tattoo marks." A Mer tattoo song also brings

out this idea more clearly:

Rama O Rama, my tattoos are of the colour of

"Hingalo [vermillion]," O Rama;

Listen, O Rama, uncle, brothers and

grand-father,

O Rama;

Mother and aunt and all return from the

gateway,

O Rama;

These tattoos are my companions to the

funeral

pyre, O Rama;

Rama O Rama, my tattoos are of the colour of

"Hingalo," O Rama.

The Dangs shared a similar belief stating,

"the marks would go with us to paradise but

if one is not tattooed, after death God will

use a red-hot ploughshare to make them."

The tattoo motifs preferred by the Mers have

a close relation to secular and religious

subjects of devotion. Designs include holy

men, feet of Rama or Lakshmi, women carrying

water in pitchers on their head, Shravana

carrying his parents on a lath (kāvad) to

centers of pilgrimage, and popular gods like

Rama, Krishna and Hanuman are also depicted.

The lion, tiger, horse, camel, peacock,

scorpion, bee and fly are other favorites.

Symbols derived from nature such as those of

the coconut, date palm, mango, and acacia

tree or champa flowers and almond nuts are

also common. Articles of daily use such as

pedestals, cradles, and even confections

occur (Figs. 26-31). Other tattoo subjects

such as shrines, thrones, wells, anchors,

chains, and groups of various agricultural

grains are found.

Mer men are not profusely tattooed and it is

customary for them to have marks placed

about their wrists, on the backs of their

hands, and sometimes on the right shoulder.

Camels are common symbols for the shoulder

and they are favorite motif, as they are for

the Rabari men of Gujarat who have them

tattooed on the back of the palm or on the

right shoulder. One authority has stated

that the placement of men's tattoos on the

right may relate to the importance of the

right hand in Hindu belief; "it is generally

associated with 'good omens' and used for

all forms of interaction with the natural

and supernatural worlds, such as eating,

writing, sacrificing, and for Brahmins,

tying the sacred cord." Other motifs common

among the men of both groups also include

Hindu inspired designs like Rama, Krishna,

or Hanuman or the om design in Hindu script

once again reflecting the process of

Hinduization among the once animistic tribal

peoples of Gujarat.

Mer girls were usually tattooed when they

were about seven or eight years old. The

hands and feet are marked first and then the

neck and breast. It is customary for a girl

to be tattooed before marriage; otherwise

her mother-in-law is likely to taunt her

that her parents are "mean or poor." One

tattooist of the Mer reported in the 1970s,

"if a bride were not tattooed, her in-laws

would protest that she had been sent to them

'like a man.'"

The indigenous instrument used in tattooing

is a reed stick having two or three needles

inserted at one end in such a way that only

about 1/4 of a centimeter of the points remain

visible. The needle points are dipped into a

prepared pigment of soot and cow's urine or

soot and the juice of the leaves of the

tulsi plant - sometimes water in which the

bark of biyān or sisam (Dalbergia lotifolia)

mixed with turmeric was used. The first type

of pigment provides a blue-black color while

the second produces a green hue. Red pigment

(mercury oxide) is also reported to have

been used by some. These pigments were

pricked into the stretched skin at least

seven or eight times to form the desired

tattoo.

A Mer woman's most favorite tattoo design is

called hānsali which encompasses the neck

and moves downwards towards the breasts. Its

name is derived from a silver necklace which

is thick in the middle and coiled at both

ends. More specifically, the hānsali begins

at the neck with a flower-motif in center

and with peacocks on either side. It is

followed below by the lādu ("sweet meat") or

bājoth (pedestal), on either side of which

occur rows of about four or five holy men.

These human figures are supposed to protect

the chastity of the women so tattooed. Next

follows two or three crescented rows, one

below the other, of enlarged deri (cover of

a churning pot) motifs with flower, bee,

etc. occurring at intervals. Likewise, the

motifs of four or five grains and pāniāri

(water pitchers) adorn the breasts

profusely. On the forearm, the tattoo starts

from the biceps and invariably has pāniāri

and peacock motifs followed by others. The

whole hand is ornamented with various

markings, the dotted designs occur

repeatedly while the linear ones appear

sparingly. On the back and sides of the palm

and the fingers two or three pairs of grain

motifs are marked. The three-grain motif

generally represents a diminutive form of

deri motif. The legs are tattooed up to the

knees, the front part of which is tattooed

more than the calf muscles. The linear

motifs like those of khajuri (date palm),

bāval tree, āmbo (mango tree), and deri

accompanied by tiger and lion adorn the

legs. The exquisite motif of the pāniāri

girdle around the border of the inner feet

is supposed to enhance the charm of the Mer

women.

The operation of tattooing is generally

executed by the experienced women of the Mer

tribe. The women of some wandering ethnic

groups like the Vāgharis and Nats also do

this work and tour the villages in the

winter. Traditionally, tattoo artists were

paid in grain, but by the 1950s all

transactions were made in cash and tattoos

were increasingly made by men with tattoo

machines.

The Rabari of the Kutch district on India's

northwest coast near the Pakistan border

also tattooed and continue to do so to this

day, although younger women who live in

urban areas are receiving fewer tattoos

because "We are now city people, and tattoos

are old-fashioned." Notwithstanding, for

hundreds of years the tribal women living in

this region have practiced tattooing for

decorative, religious, and therapeutic

purposes. Traditional patterns (trajuva)

were passed down and elder women worked as

the tattoo artists at fairs, festivals, and

markets when Rabari from the hinterlands

gathered to trade their goods and catch-up

with dispersed family members (Figs. 32, 33A

& 33B).

|

|

|

|

Fig. 32) Rabari body

tattoos |

Fig. 33A) Rabari

forearm markings |

Fig. 33B) Rabari arm

tattoos

Photograph © Michael Laukien |

|

|

Fig. 34) Various

tattoo symbols |

Tattoo pigment was prepared by mixing

lampblack with tannin extracted from the

bark of the local kino tree, or with

mother's milk and sometimes urine. A

traditional Rabari tattoo kit is simple: a

single needle and gourd bowl to hold the

liquid pigment.

Nearly all surfaces of the body are

tattooed: face, neck, breasts, arms, hands,

legs, and feet. Some Kutch tattoos are caste

marks for their particular occupations

(e.g., herders, comb-makers, or traveling

blacksmiths) while others are thought to

induce fertility or attract a husband. Still

more, usually those motifs with counterparts

in nature (e.g., lioness, scorpion, spider),

render magical protection while others

relate to religious Hindu mythology (Fig.

34). Some women believe their tattoos are

extremely appealing to the opposite sex and

that men believe tattooed women are more

faithful. Many of the Rabari motifs parallel

those of the Mer in form and function.

Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh

The Naga ethnic groups of northeast India

appear to have migrated to their present

location from Tibet sometime around A.D.

400. Naga settlements are situated amidst

mountains that slope forth into endless

successive saddles traversed by innumerable

rivers, streams, and rivulets. Formerly, all

groups were headhunters, and the Indian

government outlawed the practice in 1953;

but rumors persist to this day that men are

still on the human hunt in more remote

areas. Although most Naga tribes have

converted to Christianity, traditional

animistic religion continues to focus upon

unseen higher powers that regulate human

destinies.

One hundred years ago, tattooing was a

widespread custom reserved for women and

warrior men. Today, it is becoming

increasingly rare and its social meanings

lost. However, a large amount of detailed

ethnographic information on Naga tattooing

exists. Much of it was written in the

1920s-30s when the largely unsurveyed areas

of the Naga homelands were slowly opened up

to outsiders through the reports of intrepid

government agents, anthropologists, and

other travelers.

|

|

|

Fig. 35) Ao Naga body

tattooing

|

Fig. 36) Ao body

tattoos |

Among the Ao Naga, tattoo artists were

always old women who performed the rite in

the jungle near their village (Figs. 35 & 36).

Ao men were seldom tattooed, and it was

strictly forbidden in many villages for any

male to be present when a woman was being

marked; this rule was also followed for the

Wancho Naga of Arunachal Pradesh. The old

women with the necessary knowledge to tattoo

were only found in a comparatively few

villages, and they toured the country in

December and January. These months were

usually chosen for the operation on the

grounds that the colder it is the more

quickly the sores healed. The knowledge of

the art was hereditary in the female line,

the operators teaching it to their

daughters, who in turn taught it to their

daughters. In some villages, it was more or

less obligatory for a daughter of a

tattooist to follow her mother's profession.

It was believed that if she didn't, her life

would be filled with illness and she would

eventually waste away.

Girls were generally tattooed before

puberty, when they were from ten to fourteen

years old. Ao Naga informants interviewed in

the 1920s said that is was of the utmost

importance for a girl to be tattooed,

otherwise "she would be in disgrace and

would not marry well."

When a girl is about to be tattooed, a

bamboo mat is placed on the ground on which

she reclines. Several old women hold her

down while the operator plies her

instruments. The tool used for puncturing

the skin consists of a little bunch of cane

thorns bound on a wooden holder, which is

inserted into an adze-like head made from

the stalk of a plant. The pattern to be

tattooed is marked by the old woman on the

girl's skin with a piece of wood dipped in

the coloring matter. If a girl struggles and

screams during the tattooing, a fowl is

hastily sacrificed close-by to appease any

evil spirit that may be increasing the pain.

The puncturing is done by hammering this

instrument into the skin with a root of

kamri: a particularly heavy, sappy plant

with an onion shaped root. The black

coloring matter is then applied once more

after the blood has been washed off, and the

tattoo client is left to bemoan her sores

until they have healed. Usually the coloring

matter is made from the sap of the bark of a

tree called napthi. This is collected and

burnt in a pot on the fire. A leaf or a bit

of broken pottery is put over the receptacle

in which the sap is burning, and the soot

which accumulates is collected and mixed.

Among the headhunting Konyak, young boys

were ceremonially tattooed on reaching adult

age as a sign of manhood. Before the annual

ritual was performed, it was necessary for

the group of young men to capture at least

one head from an enemy's village. Magical

power was attached to the head and it was

believed to increase the fertility of the

crops and the men who took it. Like the

Wancho, the tattooing was usually performed

by the principal wife of the chief or ang of

the village, a woman of pure blood of the

aristocratic clan. To prick the pattern on

the face of one man took an entire day (Fig.

37). Those who could withstand the pain also

had the neck and chest tattooed (Fig. 38).

|

|

|

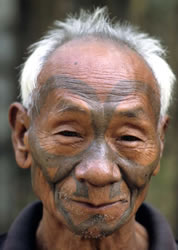

Fig. 37)Upper Konyak

facial tattooing |

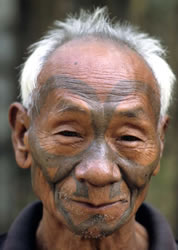

Fig. 38) Son of the

Ang of Chui, Upper Konyak, ca. 1925. |

As a Konyak man matured, he was compelled to

continue his headhunting quests. When enemy

heads were captured, they were either cut up

into pieces or brought back whole to the

village gate. The eldest male members of

each clan then performed an important

ceremony. They took a fresh egg and smashed

it against the head; then they poured

rice-beer over the head saying in a low

voice: "May your mother come, may your

father come; may your brothers come; may all

come!" The destruction of the egg was

intended to blind - by sympathetic magic -

the victim's relatives so that in the future

they would be easier to kill. Finally, the

skull feeding ceremony was conducted. This

practice was believed to influence the soul

of the victim and to call all of his

relatives so that they too may be killed and

their heads brought to the village.

Afterwards the head was placed in a basket

and hung on an enormous log drum (khom) and

then rhythms were pounded out to notify

neighboring villages of the successful

headhunting campaign. Later in the evening

the head was brought to the morung or men's

house of the clan who captured it.

Even when headhunting was officially

outlawed in the 1950s, the Konyak and other

Naga groups did not give up their tattooing

customs. Instead, they substituted monkey

skulls, carved wooden heads or even wooden

dummies for their human victims and carried

them into the village shouting songs of

victory as if they had just taken a real

enemy. Then, the tattooing ritual was

performed. Today, however, it is quite rare

to see any Konyak or Wancho man under the

age of seventy with facial tattooing. It is

a dying cultural practice that will

disappear in the next generation.

Next Page

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|