Tattooing in North Africa, The Middle East and Balkans

Article © 2010 Lars Krutak

ARAB TATTOOING

|

|

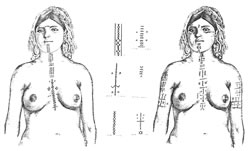

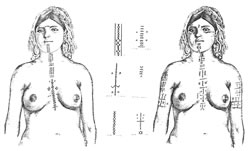

(Left) Moroccan Berber woman with chest tattooing, ca. 1920. Postcard from the collection of the author.

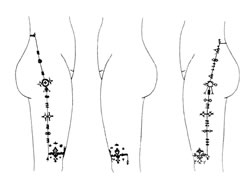

(Far left) Two Chaouian Berbers from Algeria, ca. 1916. Some of the tattoo motifs used are "star", "sun", "iron fetters," "5 and lines," "palm tree" and "mouth of the stomach." "Mouth of stomach" is thought to maintain fertility and possibly protect the navel from jnoun. Berber women also tattooed the ušam la-hmel, or "pregnancy" tattoo on their backs. |

While the Berbers have retained a distinct culture and language over the centuries, Arabs and Berbers share many beliefs, including belief in the evil eye, jnoun, and the therapeutic power of tattooing. In Iraq, Arabs placed tattoos over a region of pain to cure rheumatism, wounds, bruises, or sprains. More complex and beautiful designs were applied to Arab women for purposes of ornamentation and as enhancements to physical beauty. Arab proverbs praise the beautifully tattooed woman: “foulana tabagha khir men mra kamla,” meaning, “the limb of such a person was worth more than an entire woman.”

|

|

Of course, other forms of more “magical” tattooing existed each of which combined to create potent love charms; to guard children against death; and more importantly, to induce pregnancy in women.

The most substantial record of women’s tattooing in Iraq was compiled by Dr. Winnifred Smeaton, a physical anthropologist and fluent Arabic speaker, in the 1930s. Working as a member of the Field Museum Anthropological Expedition to the Near East under the guidance of the anthropologist Henry Field, she secured detailed information on tattooing from Iraqi tattooists and numerous women who were patients at hospitals across the country. Due to the scope and importance of this work, I will briefly paraphrase the most important aspects of her article entitled “Tattooing Among the Arabs of Iraq,” that appeared in volume 39 of the American Anthropologist for 1937. Many comparable details to tattooing practices in northern Africa are mentioned:

Women, mostly professionals, do nearly all tattooing among the Arabs of Iraq. It is not a hereditary profession, but any woman who has the skill and inclination can become a daggagah or tattooer. There are various methods of making the pigment for tattooing, which is known as kohl or basmah, but the principle is the same, for the chief ingredient is always carbon in the form of lampblack. The word kohl usually refers to the powdered antimony that is put around the eyes, but it is also used to mean lampblack, which is used by the poor in the same way as the antimony. Burning either the ordinary kerosene of lamps, tallow or a piece of cloth dipped in dihn, the mutton fat used for cooking, precipitates the carbon. Sometimes indigo is added, or bile from the gall-bladder of an ox, which sets the dye, but the commonest method is to gather the soot precipitated on the bottom of a dish held over the lamp, and make a paste. Many people hold that the soot must be moistened with halib umm al-bint, the milk of a woman nursing a daughter, which has magic properties. The use of human milk was noted in several places, always the milk of a woman nursing a girl, as the milk for a girl is supposed to be specially soothing and cooling.

In all cases the instruments used are ordinary sewing needles of varying number according to their size and the technique of the operator. Usually they are of good size, but smaller than a darning needle, from two to four bound together for at least half their length. First the design, which in most cases depends on the taste and skill of the operator, is drawn on the skin with the needles dipped in the dye, and then pricked through. The tattooed surface may or may not bleed; whether it does or not is not important, except that some women said that it is better to perform the operation in the morning because it bleeds a lot if it is done at noon.

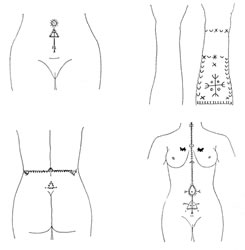

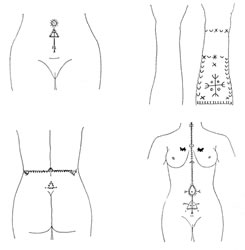

One woman had three large dots irregularly placed on the lower abdomen, as well as a design around the navel. The dots in particular were to insure her having children, but she said she had already had one child when the tattooing was applied. This was done on the third day of menstruation. A midwife also mentioned this type of tattooing to insure child bearing. According to her, the tattooing may be a single dot or a small design consisting of three to five dots, applied below the navel, or on the back just above the buttocks. It must be done on the second or third day of menstruation.

The efficacy of a third type of magical tattooing, which is a form of sympathetic magic, is aided by having someone read the Koran while the tattooing is being applied. Women practice this secretly. A woman in Baghdad had three dots tattooed in a triangle on the palm of her right hand to insure her keeping her husband's love. A similar design on the left hand would mean that the woman no longer wanted her husband's devotion. A midwife had a circle of five dots on the palm of her right hand. She said that she was her husband's second wife, and when he took a third, she decided that something must be done to ward off any possible conjuring on the part of the new wife. So one Friday noon, the most effective time, she had her right palm tattooed while a woman mullah read the Koran. The potency of the tattooing could not be doubted, for the result was that her husband divorced both his other wives and kept her!

|

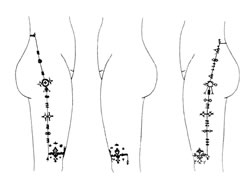

Women’s body tattooing from Iraq, ca. 1930. Winnifred Smeaton, who studied the tattooing of women in Iraq, stated that one of her informants, a midwife, said that “the cross, or as she called it, the four-sided, is the best, that is, the strongest design.” |

|

|

|

Qur’anic reading sessions for women, led by female mullahs, are ceremonial occasions termed krayas. In Iraqi Shi’a villages, these readings or recitations of Qur’anic text, often in the form of chant, or poetry, are based on time-honored Islamic traditions of oral performance that focus on narratives of ethnic origin. The mullah, working in tandem with the tattooist, moved in and out of a sacred history and space with her words to effectively convert the confines of the tattoo client’s home into a sacred sanctuary. Seen from this way, the tattoo ritual thus generated a rhythmic interweaving of patterns of worldly and heavenly life, linking women as the guardians of family traditions to the realm of the sacred. This highly personal landscape, activated by the divinely ordained words of the Qur’an and by the baraka laden tattooist and her potent tattoo pigments, created not only a physical and social space that was experienced collectively, but one that became more sacred with each repetitive instance. Therefore, just like any Muslim turns any worldly place into an individual sacred space by performing the five prescribed daily prayers to Mecca, the mullah and tattooist performed similar repetitive signifying acts. By using their speech and actions, they created their own sacred space from which their client’s tattoos took their meaning.

Next Page | 1

|

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

Museum photo gallery of the images

on this page may be seen here. |