Tattoos of Sub-Saharan Africa

Article © 2010 Lars Krutak

Spiritual Life of the Makonde

The Makonde adhere to a cosmology dominated by a powerful impersonal force (ntela), the propitiation of ancestral spirits (mahoka) who are sometimes good or evil, and a concept of pervasive bush spirits (nnandenga) and sorcerers who are believed to be a form of malevolence.

Mahoka are often called upon to send cures for sickness, and to ensure success in the harvest or in hunting. The spirits of ancestors also served as intermediaries between the living and Nnungu, a powerful deity who was invoked during major droughts when the Makonde collectively prayed for rain.

On the malevolent order, spirits of the dead called mapiko only terrorized women and the non-initiated, while sorcerers created invisible slaves from humans called lindandosa that were sent to the agricultural fields to work their evil magic.

Because excessive fear of death pervaded Makonde belief, its stigma had to be controlled or pre-empted because it threatened the basic assumptions of cosmic order on which society rested. Thus, every woman understood that her participation in society could provoke the negative intervention of powerful spiritual forces made manifest as mahoka, nnandenga, lindandosa, or mapiko who were the ultimate guarantors of social, physical, and economic survival. In this sense, Makonde tattoo arts were an important tool for fostering productive interaction between human beings and spirits, because it is clear that the designs repeatedly tattooed on women helped to secure their commitment to the potencies that bring forth life and to the socialization process of initiation itself. Tattoos also constructed a common visual language through which these relationships could be tangibly expressed and mediated to provide the individual wearer with a means to control her surrounding world.

Similarly, Makonde sculpture and more utilitarian objects like gourds (situmba) and water pots, which embody feminine and reproductive qualities, symbolically reinforced this commitment to order and stability because they were often decorated with tattoo designs. As "ancestral implements" used for carrying water, beer, honey, and seeds for planting, gourds were considered to be female symbols par excellence. And like the tattooed bodies of Makonde women, they acted as conduits through which symbolic meaning poured – meaning that connected the human, spiritual, and ancestral communities of the Makonde of Mozambique.

Malagasy Tribes

Madagascar is the fourth-largest island in the world and has been populated for nearly two thousand years. 17th century seafarers remarked about the inhabitants’ curious custom of tattooing their bodies and this tradition held fast until the early 20th century when it began to disappear from view. According to the Malagasy scholar Decary, tattooing (tombokalana, “to mark”) had already been abandoned in many parts of the country by 1950. And only traces of it could be found amongst the Antandroy, Makoa, Sakalava, Mahafaly, Antanosy, Bara and Tanala tribes.

|

|

|

| |

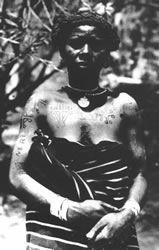

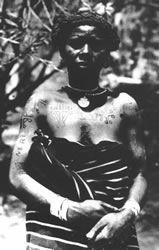

Makoa tattooing (woman) and Sakalava facial designs

(men) of Madagascar, ca. 1940 |

|

|

The operative technique was the same everywhere. The tattoo artist, using a paste made from a mixture of water and soot, stenciled the desired pattern on the skin. Then taking three or four cactus needles, the tattooist pricked the skin repeatedly while taking care to remove any excess blood as it accumulated. Into the fresh wounds was rubbed a mixture of powdered charcoal from an ear of corn and nightshade or indigo juice. The mixture quickly penetrated into the multitude of small wounds, and the color obtained was jet black and very dark. During healing, however, the epidermis was highly turgid. When the scabs fell, the tattoo became more bluish in coloration. Well made tattoos were said to last a lifetime without much fading. |

|

Malagasy tattoo patterns. Nos. 1-3 Sakalava; 4-6 Mahafaly; 7-21 Antandroy; 22-26 Antanosy; 27-28 Bara; 29-30 Tanala, ca. 1940.

|

Malagasy tattoo designs were innumerable. The Makoa, owners of very typical decorations, influenced their neighbors the Sakalava with their patterns which were mostly worn by men. Prominent among the Makoa were tattooed sets of straight lines or curves, simple or branched, with combinations of angular lines and points on the forehead, nose, and cheeks. Oblique lines, straight or curved, originated near the ear and ran to the corners of the mouth. On the chest, a single or double “necklace” spanned one shoulder to the other in a regular curve, and when a second line was tattooed it consisted of “suns” and stylized human figures that were cross looped in cruciform or swastika-like forms.

Women wore similar cross-like elements on their backs – especially on their shoulder blades and even down the back to the kidneys – that sometimes combined “solar wheels” and human figures into composite designs. On their arms crosses, triangles, anthropomorphs, and crocodile motifs were common.

Among men of the Sakalava, single and double lines framed the forehead and semi-circular elements crossed over one or both eyes. V-shaped tattoos and single lines sometimes adorned the areas beneath the eyes and cases of linear asymmetry were frequent, especially on the cheeks where complex shapes were quite varied. The rest of the male body offered little tattoo diversity: “necklaces,” “sun wheels,” and other marks circled the wrist. Sakalava women wore similar designs yet they were typically more complex and dense in their patterning.

Each tattoo design among the Sakalava had individual names but only the masoandro or “solar road” had a special meaning that was not forgotten: it served to "illuminate" the pathway that cattle thieves followed when working at night. Women also placed this favorite motif between their breasts and other seductive locations to increase their skills in love because it was a symbol of strength and virility.

In the Mahafaly and Antandroy region, large cross-like forms ending in circular elements were the favored design for a woman’s face, breasts, and back. The arms of men and women were also covered with the names of lovers, husbands, and wives. Some women were seen with five or six names side by side or superimposed in case there was a lack of space.

Further north among the Tanala, tombokalana were very characteristic and almost exclusively reserved for women. These tattoos consisted of rows of parallel lines, straight or broken, that decorated the chest, arms, face and calves. On the back, they were only found on the region of the tailbone and buttocks and were said to be “erotic.” |

|

|

| Antandroy tattooing, early 20th century. |

When Decary asked about the purpose and meaning of the tattoos, he received everywhere the same answer: "These are ornaments, objects of flirtation, which is why they are worn mainly by women." An Antanosy woman added: "These are jewels we have in the skin."

Despite the generality of these replies, Decary concluded that in the past Malagasy tattoos probably served ritual purposes. “Their original meaning was magical but lost in the mists of time,” he wrote. “And now they are almost always ornamental.”

This, he explained, was why tattoos were becoming rarer in men than in women: [ladies] considered them only as an additional attraction because it enhanced their beauty.”

Today, all of these ancient tattoo forms have disappeared. But this is not surprising since one of Decary’s informants predicted this outcome nearly sixty years ago: "The earth is civilized [now]; it is no longer as it once was."

Next Page | 1

|

2 | 3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

Museum photo gallery of the images

on this page may be seen here.

|