Shamanism, Blood Sacrifice, and Tattoos

For millennia, nearly all indigenous

people who tattooed practiced shamanism

which is the oldest human spiritual religion

born at the dawn of time. Death was the

first teacher, the edge beyond which life

ended and wonder began. Shamanistic religion

was nurtured by mystery and magic, but it

was also born of the hunt and of the

harvest, and from the need on the part of

humans to rationalize the fact that they had

to kill that which they most revered:

plants, animals, and sometimes other men who

competed for resources or whose souls

provided magical benefits.

Mythology developed out of these

associations as an expression of the

covenant between humans, their environment,

and everything contained within it. But more

importantly, it was a means of eliminating

the guilt of the hunt, whether human or

animal, and maintaining a certain essential

balance between the living and the spirits

of the dead. After all, shamanism is

animism; the belief that all life - whether

animal, vegetable, or human - is endowed

with a spiritual life force. Spirits living

in these objects were always propitiated and

never offended. Sacrificial offerings,

especially those made in blood, were like

financial transactions that satisfied

spirits because they were essentially "paid

off" for lending their services to humankind

or to satisfy debts like infractions of a

moral code which most indigenous peoples

around the world observed. For example, the

heavily tattooed Iban of Borneo respect adat

or the accepted code of conduct, manners,

and conventions that governs all life. Adat

safeguards the state of human and spiritual

affairs in which all parts of the universe

are healthy and tranquil and in balance.

Breaches of adat disturb this state and are

visited by "fines" or contributions to the

ritual necessary to restore the balance and

to allay the wrath of individuals, the

community, or of the deities. Traditionally,

such rituals included the sacrifice of a

chicken, pig, or in special instances even

another human - especially when a new

longhouse was built.

|

|

|

|

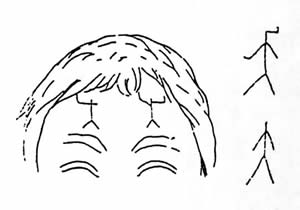

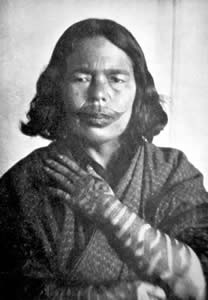

Chukchi woman with three fertility

tattoos on cheek and a cruciform

tattoo foil marking the corner of

her mouth that was intended as a

charm against evil spirits. Foils

were also stitched into living skin

if the individual had been in great

danger and had escaped. After the

death of a near relative, the

Chukchi also fastened a single bead

to a lock of hair to repel the

"spirits of disease." Chukchi

warriors who had killed other men

sometimes tattooed anthropomorphic

stick-figures on their shoulders in

hopes of capturing the soul of their

victim, thus transforming their

"foe" into an "assistant" or even

into a part of himself. Photograph

ca. 1900. |

|

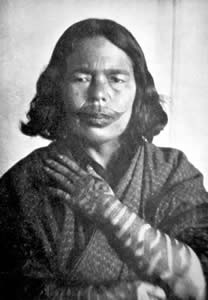

Qayaghhaq, one of the last

completely tattooed St. Lawrence

Island ooing, "We did it to be

beautiful, so that we would not look

like men. We wanted precious

pictures for the afterlife." She

also wears a set of three fertility

tattoos on her outer cheek and qilak

or "heavens" tattoos near the ear.

Beautifully executed tattoos such as

these were believed to lure game

animals near. In turn, they brought

into the house a part of the sea and

along with that, part of its animal

and spiritual life. Photograph ©

Lars Krutak 2009-1997 |

Perhaps the most common and important

blood sacrifice practiced by many tattooing

cultures worldwide was headhunting: the

taking of human heads for ritual use. Human

blood, the fertilizing essence of everything

animate, was a highly revered sacred

substance believed to appease spiritual

powers that controlled the forces of nature.

Among the prehistoric and tattooed peoples

of ancient Peru like the Moche, Tiwanaku,

and Chimú, ritually prepared human heads

were perceived as potent sources of power to

be harnessed and tapped in order to promote

agricultural fertility and relations with

the ancestral dead and deities. Analogs

drawn from historical headhunting cultures

of India, Borneo, the Philippines, Taiwan,

China, and Brazil also support this model;

because the ritual taking of human heads in

these places was accomplished to ensure both

biological and agricultural fertility, among

other magical advantages.

Apart from their role as the guardians of

tribal religion, some shamans actively

participated in tattooing traditions

themselves. Among the Paiwan of Taiwan, the

Chukchi of Siberia, and the Yupiget of St.

Lawrence Island, Alaska, female tattoo

artists - who were usually shamans - worked

via supernatural channels to cure their

patients of "soul-loss" which was

attributable to disease-bearing spirits that

could be either human or animal. Sometimes

proper treatments included the application

of medicinal tattoos at particular points on

the body or "tattoo foils" to disguise the

identity of the sufferer from such

malevolent entities. Of course, the Chukchi

and Yupiget also tattooed fertility stripes

on the cheeks of barren women or stick-like

anthropomorphic "guardian" markings on the

foreheads of men and women to harness

ancestral powers. In all cases, Paiwan,

Chukchi, and Yupiget shamans were proactive

in rearticulating the surfaces of their

patient's bodies by multiplying its

inscriptions and reinscribing its parts. But

the perceived efficacy of these treatments

was not only confined to the technical or

performative aspects of the tattoo

application itself - although the tattoo

pigments used by the Yupiget were considered

to be "magical" and evil spirits were afraid

of them. Rather, the shaman's power arose

from helper and ancestral spirits who

communicated their magical and curative

powers through her.

Not all tribal tattooists were shamans,

however, because some were simply

traditional healers who had particular

specializations (e.g., eyes, ears, throat).

In the northern Philippines, tattoo artists

tattooed markings on the throats of patients

suffering from goiter or other markings on

the backs of individuals plagued by skin

disorders. Yet many tribal tattooists did

work under the guidance and protection of

one or more spiritual helpers like Kayan

tattooists in Borneo who were always female.

In these instances, some tattoo artists were

like shamans in that they employed methods

of spiritual and physical medicine to "cure"

their patients of serious conditions. The

Kayan tattooed a design called lukut or

"antique bead" on the wrists of men to

prevent the loss of their soul. When a man

was ill, it was supposed that his soul had

escaped from his body, and when he recovered

it was believed that his soul had returned

to him. To prevent the soul's departure, the

man would "tie it in" by fastening round his

wrist a piece of string on which was

threaded a lukut within which some magic is

considered to reside. Obviously, the string

can get broken and the bead lost so the

Kayan replaced it with a tattooed bead motif

that has come to be regarded as a charm to

ward off all disease.

Interestingly, the Kalinga of the

Philippines have a related belief. When

blood is inadvertently drawn in the village,

including that which flows during a

tattooing session, a sipat gesture is made.

The sipat is similar to an exchange of peace

tokens, and begins with the sacrifice of a

chicken whose blood is rubbed near the

injured body part. A brief chant is given to

ward off any evil spirits, and then a red

carnelian bead (arugo) on a string is placed

around the wrist of the person who was

injured. This bead is also a protective

device against malevolent spirits; it "pays

off" any spirit in the vicinity. The

Mentawai of Siberut Island also wear

intricate bead tattoos on the backs of their

hands. One man told me that these permanent

beads "tied-in" his soul to the body but

that they also made him more skillful

whenever he needed to use his hands to

perform various tasks. It should be noted

that the Mentawai people are one the most

profusely tattooed people living today and

the reason for this, they say, is that their

beautifully adorned bodies keep their souls

"close" because they are pleased by

beautiful things like beads, flowers,

sharpened teeth, facial paint, and above all

tattoos (titi).

Before the advent of modern

medicine, many Kalinga women of the

Philippines had small marks tattooed

on their necks to cure goiter. Fagki

wears these marks but she also

suffers from the affliction.

Photograph © Lars Krutak 2009-2007 |

|

Of all Kalinga tattoo motifs, centipedes and python scales seem to dominate. Both creatures were considered "friends of the warriors" (bulon ti mangayaw) and are believed to be earthly messengers of the most powerful Kalinga deity Kabunian - the Creator of all things. Many women proclaimed that their skin didn't wrinkle if fortified with these designs and that their beautiful body tattoos increased their fertility. Other tattoos were also natural symbols derived from nature. XXX's represent rice bundles and /\/\/\'s are the steps of rice terraces. Some women were tattooed with "necklaces" to appear permanently beaded and beautiful.

Photograph © Lars Krutak 2009-2007 |

Tattooing Techniques and Magical Referents

Tattooing has always been a creative process and depending on local environmental and cosmological forms and meanings, tattooing techniques were quite varied. In Papua New Guinea and other insular regions of Southeast Asia like the Philippines and Taiwan, lemon or orange thorns were utilized in hand-tapping tools; whereas in Polynesia hand-tappers preferred comb-like instruments forged from animal bones. In Sub-Saharan Africa, groups like the Makonde practiced skin-cut tattooing by carving designs into the living flesh with iron tools made by the blacksmith and then rubbing-in carbon pigments derived from the castor bean plant. The Native peoples of the Northwest Coast of North America like the Haida and Tlingit used hand-poking tools probably derived from Japanese sources although they are much smaller in scale. Each pigment brush was carved with a crest animal that imparted supernatural protection to the design thus created. Other indigenes like the Ainu of Japan and several Native American groups in California like the Hupa preferred obsidian lancets with which to slice open the skin; afterwards a sooty pigment was rubbed into the raw wounds until the skin felt like it was "on fire." Both groups practiced medicinal forms of tattooing and also more supernatural forms aimed at blocking evil spirits from entering the orifices of the body. Amazonian groups preferred various varieties of palm thorns to prick-in their tattoos, while the pre-Columbian Chimú seemingly skin-stitched their tattoos with animal bone or conch needles attached to sinew or vegetable threads - such tools have been found in mummy bundles.

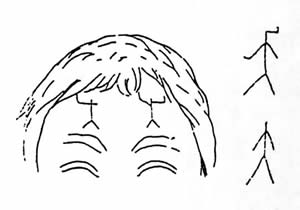

"Guardian" or "assistant"

tattoos. In the Siberian Yupik

language these marks are called yugaaq or "powerful person" and

recall an ancestral presence.

Drawing ca. 1900.

|

|

|

|

A Laju Naga women

living in Arunachal Pradesh, India

reported that, "My ancestors will

only recognize me after I die

because of my tattoos." Photograph ©

Lars Krutak 2009-2008. |

The technique of skin-stitching was also practiced by more northerly Arctic peoples like the Yupiget, Chukchi, and Inuit until the early 20th century: a practice believed to be over 2,000 years-old. Tattooing here was always performed by women and tattooing in the traditional manner required extensive knowledge of animal products, pigments, and natural substances suitable for indelible marking. In the Yupiget and Chukchi areas, Lampblack was the primary pigment used to darken the sinew thread because it was believed to be highly efficacious against "spirits." However, fine dark graphite (tagneghli) was also used. Tagneghli was a magical substance obtained through barter in Siberia, and it was considered to be the "stone spirit" which "guards" humankind from evil spirits and from the sicknesses brought by them. Traditionally, it was used to protect village children from the possessive spirits that were "awakened" as a result of a recent death in the village. Lampblack or graphite was then mixed with urine (tequq) because it was also considered to be an apotropaic substance suitable for tattooing, perhaps because it came from the bladder: an organ believed to be one of the primary seats of the life giving force of the soul. In this connection, it should come as no surprise that some Yupiget elders of St. Lawrence Island told me tequq was poured around the outside of their traditional semi-subterranean houses called nenglu because "many years ago, urine was very special. It scared away the evil spirit."

|

|

|

The intricate tattoos that appear on

the wrists of the Mentawai people of

Siberut Island, Indonesia are called

ngalou or "beads," but this word

also means "talisman." Like the

Kayan lukut tattoo of Borneo they

"tie in" the soul and keep it close

to the body. The rosettes tattooed

on the shoulders of men (sepippurat)

like shaman Aman Lau Lau (pictured

here) symbolize that evil should

bounce off their bodies like

raindrops from a flower. Photograph

© Lars Krutak 2009-2007. |

Kayan woman with hornbill,

"shoots of bamboo", "guardian

spirits," "dragon-dog," and tuba

root motifs that are all believed to

repel evil spirits. Floral imagery,

symbolizing spiritual powers and

relationships, permeates every facet

of Kayan life. Plants are regarded

as a major kind of living thing,

sharing the same fundamental

properties of life and death as

humans. Photograph © Lars Krutak

2009-2002. |

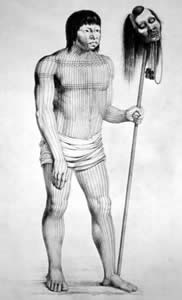

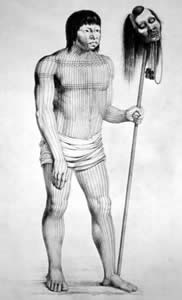

Full-body tattoos of a Mundurucú warrior with head trophy, ca. 1810. For these dwellers of the Brazilian Amazon, mythology states that their tattoos were given to them by their Creator god who had several avian characteristics. Tattooing for both men and women consisted of fine, widely spaced parallel lines applied vertically on limbs and torso, each motif reminiscent of an abstract series of long bird plumes enveloping the body. Human head trophies were believed to please the "spirit mothers" of the game animals thereby increasing the yield of the hunt and making game more tractable to the hunter. |

Buddhist monks in Thailand, Cambodia, Myanmar, and Laos utilize tools that resemble a sharp two-foot long metal skewer split at one end about two inches to form a needle-sharp pronged tip. The space created between the two needle tips acts as a reservoir to hold the tattoo pigment. These tools look much like a shish-kabob used to barbeque meat and vegetables on the grill. In Thailand, each tattoo is created by a master monk called an arjan. The inks that the monks use are personal recipes, and some are thought to have special "protective" qualities due to their unusual and magical ingredients. For example, some arjans use sandalwood, steeped in herbs or white sesame oil. Oil extracted from wild animals such as elephants in must, galls of tiger, bear and even cobra venom or the chin fat from a corpse are said to be used. Others mentioned that the exfoliated skin of a revered arjan was added to Chinese ink mixed with holy water to make their tattoo pigments. In these cases, it is believed the tattoo thus created from such an ink would cause those people who interact with the wearer to behave as if they were in the presence of a monk; that is, the tattoo would cause them to be somewhat reverent and treat the bearer of the tattoo with respect, among other things.

|

|

|

Before a Buddhist tattoo master or

arjan gives a tattoo, he must first

read your aura to determine what

design you need. Magical tattoos of

this type have power because they

not only draw on the power of the

tattooist, but also his mentors, and

the Buddha and his teachings. These

are all sources of power (kung). In

this way, Thais who follow Buddhism

operate with a set of assumptions

about the nature of the world, the

beings and forces within it, and the

ways these are related. These

beliefs form an integrated system of

ideas and propositions that they use

to interpret the world and organize

their daily actions. In some cases,

enemies can be turned into friends

with specific tattoos, while others

provide their owners with personal

protection, commanding and

attractive speech, adding to a

person's sacred virtue.

Photograph ©

Lars Krutak 2009. |

|

A Khiamniungen Naga warrior from the

Myanmar/India border with "tiger

chest" tattoo. His V-shaped torso

markings not only indicate that he

is a successful headhunter, but that

he could become "tiger-like" when he

struck down his enemies. Photograph

© Lars Krutak 2009-2007. |

|

|

Ainu woman of Japan with bold facial

and forearm tattoos that worked to

repel evil spirits from entering her

body. The Ainu also practiced

medicinal forms of tattooing to

relieve rheumatism. The last Ainu

woman with tattooing died in 1998.

Photograph ca. 1900.

|

The Art of Magical Tattoos

For thousands of years tattooing has been as much of a statement of worldviews in which humans, nature, and the supernatural landscape united as it has been an interlaced fabric that documents a range of ideas about the sacred geography of the skin - our most natural canvas. Tattooed images reveal a close relationship between humans and the rest of nature, and in the cosmology of the tribal tattooist humanity was thought of as an integral part of life's web on every level of existence. In the animistic universe, natural and supernatural forces were propitiated, cajoled, and appealed to for the benefit of humankind, because indigenous peoples sought to acquire access to the power of various animals, spirits, and the ancestors. But more than just skin deep symbols tattoos established visible linkages between these spiritual and natural domains by tapping into them, allowing the body to escape into a world where there was nothing but the magical essence of things detached from the here and now.

Museum photo gallery of these images may

be seen here.

|