Tattoos of Indochina: Supernatural Mysteries of the Flesh

Article © 2010 Lars Krutak

For over a thousand years, tattooing has been a significant part of religious life among the peoples of Indochina. Integrated into a system of belief encompassing Theravada Buddhism, Hinduism, animism, and ancestor worship, tattooing evolved into a kind of magical text that adherents used to navigate through an uncertain, unpredictable, and imperfect world dominated by human enemies, deities, nature spirits, and the dead.

|

|

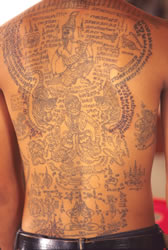

Largely administered by holy monks, sagacious tribal elders, and layman tattooists, the esoteric art was not only believed to provide its wearers with indelible protection from a variety of misfortunes, but also the mystical power to influence other peoples’ behavior, carry the deceased safely into the afterlife, or simply increase a person’s “luck.” Whatever the personal motivation may be for receiving these sacred and lasting symbols, tattooing in contemporary Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam continues to firmly anchor the religious faith of its devotees on human skin for all to see. Although many traditional motifs have been replaced with modern versions of ancient designs, the desire to be marked with powerful amulets remains. Why you may ask? Because tattoos are seen as magical mediators between this world and the next that are capable of channeling powerful cosmic forces that transcend nature, the mind, body, and soul. |

|

|

|

|

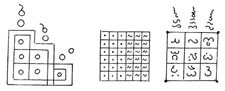

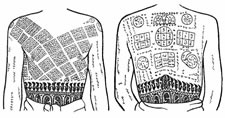

Laotian tattoos that protect the wearer from bullets, 1940. |

Laotian tattoos that protect the wearer from animal bites and render the individual “invulnerable.” |

More magical tattoos from Laos, 1940. The first tattooed symbol was believed to protect the wearer from daggers, arrows, and bullets. The second is a love charm. |

Tattooing Monks of Indochina

|

|

Thai Buddhist monk administering a sakyan or magical tattoo to a faithful devotee. Outside of the esoteric religious traditions of tattooing, historians have also traced the indelible practice to an extremely elaborate code related to administrative purposes in Thailand. In the 18th century, army officers (arms) and couriers (wrists) wore specific tattoos to distinguish them from other sections of the military. A person exempt from corvée through some infirmity or defect could obtain an exemption tattoo (sak phikān). Someone too old for corvée could obtain a mark for the aged (sak charā). Even individuals who cut grass for elephant fodder also wore a specific tattoo (sak pen taphun yā chāng) as did slaves and their children. Criminals who had been found guilty of some crime against the state received a mark (or marks) on the face. And individuals who faked an administrative tattoo insignia could be put to death, together with their entire family. Photograph © Lars Krutak |

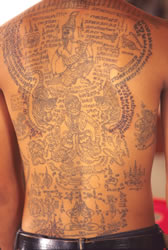

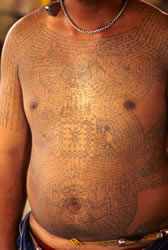

Most tattooed people in Indochina will tell you that the real magic of their tattooing comes from the Theravada Buddhist monk who probably created it. Therefore it should come as no surprise that even the smallest and poorest towns and villages throughout Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Myanmar maintain temples and tattooing monks (called arjans in Thailand or sayas in Myanmar). Animal figures like the tiger, tortoise, and others from the Hindu pantheon (e.g., Hanuman, Garuda, etc.) are part of the magic of some tattoos, but many other human skins are also inked with holy katha or magic spells and diagrams (called ang by Shans in Myanmar) written in Khom (Thailand, Laos, Cambodia), the sacred calligraphy of the ancient Khmer language, or Pali (Myanmar), the sacred canonical text of Indian origin. Other spells and prayers are sometimes tattooed in Sanskrit.

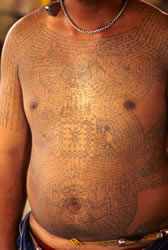

Cabbalistic tattoos worn by a Shan man in Burma, ca. 1930. Among the Shan, a reddish tattoo pigment that gradually disappeared was also used to ink patrons. More specifically, this color was used in designs to induce “love magic.” The colonial administrator Sir James George Scott wrote in 1896: “This ‘drug of tenderness’ is composed of vermillion mixed with a variety of herbs and curious things, prominent among which is the bruised, dry skin of the touk-the, the trout-spotted lizard, whose sonorous cry and fidelity to the house where he establishes himself and brings luck, are well known to all who have visited Burma. It is very sparingly used, a few round spots arranged in the shape of a triangle being of sufficient virtue to ensure the object aimed at. The commonest place for them is between the eyes, but occasionally the [tattooist] recommends the lips, or even the tongue, and his advice is always followed. This is the only tattooing which women ever have executed on them, and there are not many of them who have it done.” |

|

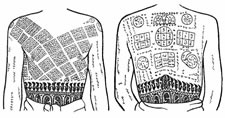

Magical torso tattoos from Laos, ca. 1920.

|

Katha are taken from verses of the Buddha’s teachings and are either written out on the flesh or encoded in cryptic diagrams that only master monks know. Katha and diagrams are used in every category of Theravada Buddhist tattooing and particular verses depend on the function of the tattoo itself. Although there are various levels of katha magic, the power of the inscription ultimately depends upon the level of power embodied in the monk who gives it – a topic I discuss in more detail below.

Before a tattoo master or arjan gives a tattoo in Thailand, he must first read your aura to determine what design you need. Of course, when I made the trip to one of the most famous tattooing temples at Wat Bang Phra, everyone wanted the ancient 8-pointed compass tattoo because it is not only empowered with highly protective magic, but Wat Bang Phra is the only temple in Thailand that offers this tattoo. Speaking about the beautiful birds tattooed between the shoulder blades, one man told me: “When I talk from now on, everyone will listen to me because my voice will be like the beautiful music of these songbirds.” Photograph © Lars Krutak. |

|

|

| |

The Indian hermit Ruesi (above center) is worshipped by arjans and their clients, because it is believed that these men brought tattooing to Thailand in the distant past. Ruesi are also important in traditional Indian mythology because they act as intermediaries between humans and deities. Photograph © Lars Krutak. |

As with all magical tattoos of this sort, the monk making them recites katha just before, during, or after his tattooing session. These versus may be voiced in a whisper or mumble barely discernable to the client. Regardless of the method of delivery, the power of the tattoo will not work for the tattoo recipient unless he continually obeys at least one of the five Buddhist precepts during the course of his life. Therefore, and in their attempts to maintain the magic of the tattoo, men are careful to observe one or more of the following fundamental doctrines: refraining from killing, stealing, lying, intoxication, and/or the pursuit of improper sexual behavior. (Note: I use the pronoun "he" since it is men, not women, who typically wear these powerful pigmented tattoos, although some monks will tattoo women with invisible oil tattoos in Thailand or more rarely with pigmented tattoos in Myanmar or Laos.)

|

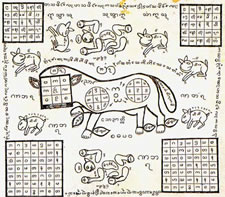

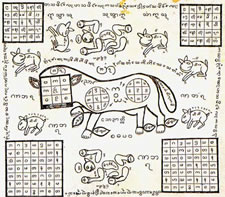

| Paper scroll from the Shan area with mystical animals and magical formulae (ingwet). Such scrolls were often burnt then dissolved in water and drunk as part of induction ceremonies for tattooing monks. |

|

| Jack works in a Thai shipyard. He told me that he was in the hold of an oil tanker and a fire broke out in the machine room. The electronic safety doors began to close to cut off the fire from spreading, and a slick of burning oil was moving towards him. Then, the slick suddenly moved around him in a circle and he believes his tattoos protected him from being burnt alive. He banged on the safety doors, and in a few minutes he managed to escape the ship unharmed. Also note the numerous protective amulets and charms he wears on a cord wrapped around his waist. Photograph © Lars Krutak. |

Of course, older and more devout people may choose to follow eight precepts including the aforementioned five plus abstaining from meals at noon, entertainments, and sleeping on a high and wide bed. Not surprisingly, the more precepts a person is able to keep, the greater the strength of their tattoos!

Yet it has also been recorded that specific human actions can "dissolve" the power found in their tattoos. A medical officer in Burma wrote in 1959 that men wearing magical tattoos may not enter a laboring room within one week after a baby was delivered there. "If they do they may lose their potency or 'glory of manhood.'" Tattooed men were also dissuaded from simply visiting the house were a baby was recently born, and if they did "they must cleanse themselves with water into which a gold or silver coin has been placed [while stating] a special prayer at the same time. This is almost certainly based on Hinduism where the uncleanliness of a woman who is menstruating or post-partum is much stressed."

Regardless of these and other taboos, scholars argue that tattoo spells (katha) have power because the "sacred" words have power. But others suggest that it is not the words themselves that have power but rather their source and the circumstances under which they were learned. For example, one cannot simply memorize a katha and expect it to be efficacious. One must learn the katha from a pious teacher or monk with whom one has established a proper ritual relationship because these individuals have kung: a kind of power that not only relates to the physical components of the body, but also to kindness, beneficence, or a favor for which the recipient should show gratitude and respect. Beings like Buddhist monks with kung are powerful, and if people enter into the proper relationship with them then they have access to that power. Thus, by keeping precepts and being an honorable person, monks can create power for themselves which can be passed on to their students and clients through tattooing.

Aside from such efficacious chants, men while in monkhood have access to other kinds of powerful knowledge that can be used to increment their power. This type of power accrues to them by following the Buddha’s precepts, but also through the practice of personal discipline: and through the teachings of elder monks who represent the lineage of every monk that came before, including the Buddha and the objects associated with him. All of these powers augment those of a tattooing monk whenever he undertakes a new tattoo.

Tattooing monks must also practice restraint. Without this, they do not have power of their own or access to the power of their teachers and the Buddha. Practicing restraint means keeping precepts and being honorable. In turn, monks should keep the five basic precepts at all times, and this level of restraint and withdrawal from the world provides sufficient power to give protection to others through blessings embodied via magical tattoos (called sakyan in Thai). Most importantly, however, and assuming a monk has interest and the necessary dexterity to become a tattooist, he must acquire the knowledge and power required to make effective tattoos. This necessary knowledge takes the form of katha used in making tattoo “medicine” and reciting these spells while tattooing. Because all katha are recited from memory, master tattooists must have an extensive repertoire of them or else their tattoo magic will be, for the most part, ineffective. One monk told me: "You can’t take getting or giving a tattoo lightly. You have to be physically and mentally prepared every time you do it. It took me ten years to master the art and science of tattooing, including the memorization of the sacred scripts [katha] that I tattoo onto my patron’s bodies. All great tattoo masters must do this." And in this way, tattoos have power because they not only draw on the power of the tattooist, but also his monk mentors, and the Buddha and his teachings. These are all sources of power (kung).

|

|

|

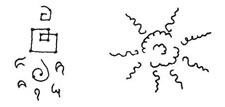

Burmese tattoo designs with their translated names. |

Burmese tattoo designs with their translated names. |

Burmese tattoo designs with their translated names. |

A Monk’s Tattooing Kit & Other Magical Devices

|

|

Burmese tattoo tool from the collection of the author with "elephant man tattoo weight, ca. 1920. There are many varieties of tattoo weights and each figure is believed to add specific power to the tattoo itself. For example, the figure of Zawgyi, an alchemist who is endowed with supernatural powers, would have been used when tattoo designs of a religious or protective nature were given. Tattoo weights with portrayals of Bawdithada were also believed to impart strength and protection. A tattoo weight depicting Mintha, a hero prince of Burma, was likely employed when designs were applied to a man’s body for beautification purposes. And weights that incorporated Belu demons holding a badashinlon (live mercury ball) or wish fulfilling stone were also supposed to impart luck. The example pictured here probably fulfilled a similar purpose because it likely represents the Hindu god Ganesh. Of course, the elephant is also associated with great strength which is another attribute that tattoo clients wished to incorporate into their bodies. |

The tattooing tools I have seen in Thailand resemble a sharp two-foot long metal skewer split at one end about two inches to form a needle-sharp pronged tip. Similar devices are also used in Myanmar but they are heavier, shorter, the pronged tip is stouter, and the tool is capped off with a tattoo “weight” that takes the form of a deity or other powerful personage. Gold and silver tools were said to have been made for members of the Burmese royal family but none of them have survived to this day. Nevertheless, the space created between the two needle tips acts as a reservoir to hold the tattoo pigment. In Thailand, these tools look much like a shish-kabob used to barbeque meat and vegetables on the grill.

Some monks use a pointilinear style, while others achieve fine line-work that looks very machine-like. The inks that the monks use are personal recipes, and some are thought to have special “protective” qualities due to their unusual (and magical) ingredients. For example, some arjans in Thailand use sandalwood, steeped in herbs or white sesame oil. Oil extracted from wild animals such as elephants in must, galls of tiger, bear, python and even cobra venom or the chin fat from a corpse are said to be used. Others mentioned to me that the exfoliated skin of a revered monk was added to Chinese ink mixed with holy water to make their tattoo pigments. In these cases, it is believed the tattoo thus created from such an ink would cause those people who interact with the wearer to behave as if they were in the presence of a monk; that is, the tattoo would cause them to be somewhat reverent and treat the bearer of the tattoo with respect.

None of the men who enter a monk’s working space mumble a word before they are tattooed, and usually two male friends will stretch the client’s skin for the tattooist. Some tattoo patrons begin to shake and go into light trances while being tattooed, while others go into deep meditation. Other than the occasional grunt from a semi-possessed client, the areas around which the monks work remain eerily quiet. Regardless of the patron, who may be possessed or not, the monks continue to work the pigment under the skin only stopping to wipe off the flowing blood. After the tattoo is complete, the monk mumbles a prayer, and blows on the tattoo to activate its magical power. This action also fuses the patron with the monk’s meditative and transcendental powers, as well as that of the Buddha's.

Next Page | 1

|

2 |

3 |

4 |

Museum photo gallery of the images

on this page may

be seen here. |