Wen Shen: The Vanishing Art of Chinese Tribal Culture

Article © 2009 Lars Krutak

Tattooed Headhunters of Taiwan

As noted previously, the earliest Chinese account of tattoo on Taiwan

was written in the seventh century A.D. and appeared in the text

entitled History of the Sui (636 A.D.). Although the reference is brief,

I think there may be some truth to it since the Paiwan have a long

tradition of tattooing abstract motifs of the hundred-pace viper on

their bodies. These serpent designs adorned the skins of headhunting men

and were especially significant because they recounted mythological

origins. The hundred-pace viper is considered to be "the spirit of life,

the greatest of all the spirits" and represents the guardian spirit of

the Paiwan people.

Men and women's tattoo marks differed according to the social status

of the wearer and tattooing was generally a privilege of the Paiwan

nobility, but a commoner could purchase the right from a "big chief."

Paiwan tattooists were mostly professional women who inherited the

occupation through the family line. Each village had one or two artists,

but most were aristocrats by birth and at the same time shamans (as

opposed to male shamans amongst the Li of Hainan). Paiwan tattoo artists

received payment from all clients, except members of the ruling chief's

family. The amount of reward differed according to the complexity of the

design chosen. For example, the cost of tattooing a man's chest, back,

and both arms was high: one pig, two iron rakes, four waist knives, one

axe, one roll of cloth, one porcelain bowl, and a bottle of wine.

Paiwan tattoo artists used bamboo splints or grass stems as rulers,

and the back of a knife covered with soot as a pencil to draft the

desired motifs. Tattoo needles were made by binding a pair of steel

needles with linen thread on a bamboo stick about 40cm in length. The

needles were again wrapped with linen thread, and only 2-3cm of the

point could be seen. A small knife was used to tap the needles with soot

pigment into the skin, and the handle of this instrument was also used

to scrape away excess blood. Before the introduction of steel needles,

the Paiwan used thorns of the mountain orange as a tattoo needle.

Like other tattoo cultures in Southeast Asia, Paiwan men and women

were tattooed in the winter in the belief that the wounds would heal

more quickly in the drier air. The ritual operation was performed in a

small hut specifically built for the purpose. To prevent intruders, a

bamboo stick was erected in front of the hut. The client usually

reclined during the operation, but women who were to receive hand

tattoos sat upright. Each unit of the design was punctured

repeatedly, up to three or four times.

|

|

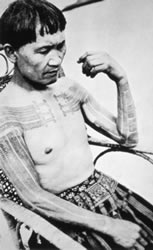

Rukai chief

and headhunter's tattoos, ca. 1900.

Among the Rukai and Paiwan, it was

believed that the spirits of their

ancestors dwelled in their beheading

knives which were held in the

possession of the tribe for several

generations.

However, the Paiwan were not

necessarily tattooed after having

taken a head. Instead, the

successful warrior was also denoted

by the wearing of a certain kind of

cap which was woven by women of the

tribe. |

Prior to the operation, the tattoo client had to present the ruling

chief with ceremonial beverages: for it was the chief who decided the

appropriate day of the tattooing. Offerings were made to the spirits of

the ancestors and various taboos were observed. During the operation,

the tattooist spat betel nut juice on the tattooed area to stop

excessive bleeding.

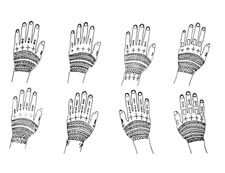

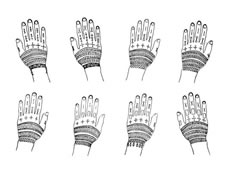

Paiwan women tattooed their arms, the backs of their hands, their

knees, and the calves. The designs consisted mainly of lines or dots.

Paiwan men tattooed the chest, arms, knees, and calves. Sometimes the

motifs were realistic consisting of human heads, human figures, serpent

or solar designs.

A related tribe, the Rukai, also employed female shamans as their

tattooists. Before the first marks were laid on the skin,

prayers and offerings, consisting of glass beads and betel nuts, were

given to guardian spirits in order to protect the tattoo client from

evil spirits aroused by the bloodletting. Other ceremonial taboos tied

to the tattooing included: no sexual relations immediately before the

operation; no tattooing while a corpse lay in the village or when a

woman was menstruating; no ingestion of animal blood before the

tattooing; and no use of red-colored clothing during the operation.

Next Page

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|