|

|||

| Celeb Tattoos | Facts & Stats | Designs & Symbols | History | Culture | Links | Tattoo Galleries | Contact | |||

|

|||

|

Crest Tattoos of the Tlingit and Haida of the Northwest Coast Article © 2006 Lars Krutak The Tlingit and Haida, as well as other Northwest Coast peoples, used animal emblems as crests (totems) to identify the different social divisions among their society. Crests were also employed to affirm a group's territorial claims. One's moiety, clan, and house (lineage) each owned a crest or several crests. Crests included, for example, land animals (Bear, Wolf), sea animals (Killer Whale, Halibut, Shark), birds (Eagle, Thunderbird, Owl), as well as geographical features (Mountain, Iceberg), celestial bodies (Sun, Big Dipper, Moon) and natural materials (Copper, Clay, Yellow Cedar). The possession of these crests by moiety, clan, subclan, or house derive from events that the Northwest Coast peoples recount in their oral traditions, events that account for their unique identity as a distinct group. Oberg succinctly describes the nature and function of crests for the Tlingit as ways of explaining the existence of their world. Crests are honored as an individual's and group's link to the wider world in which they live, linking them to creatures or things in the natural environment and to other Tlingit clans and their membership via the demarcation of rank and group identity in the social milieu. Furthermore, crests chronicle the origin of supernatural and significant events in the history of the clan. They serve as title to the object on which they are placed and to the site and geographic region where these events occurred. Crests symbolize the special relationship a clan member has to the animal depicted on the crest since the crest embodies the spirit or being depicted in the crest. Thus, the crest, and the right to use it in stories, sets the group apart from other groups while defining its position with respect to other groups. Therefore, the ownership of a crest, the right to use the emblem, was more valuable than the possession of a particular physical object, an heirloom or crest object itself. The concept of at.óow among the Tlingit describes this special form of possession not only of physical things, but also of the identity of a house or clan by its members. At.óow literally means "an owned or purchased thing," and also refers to both tangible and intangible property embodied within crest objects themselves, such as personal names, stories, songs, spirits, or even geographical features/locations. For example, the Chookaneidi clan of Hoonah, Alaska uses a glacier as their crest. They refer to the land of Glacier Bay, the glacier itself, the visual image of the Woman in the Ice (their ancestor who was covered by the glacier, "purchasing" it with her life), the story and the songs explaining the origin of the crest, and the physical and spiritual ancestor herself as at.óow. The right to a crest was not necessarily exclusive, however. Claims to a crest were contested and evaluated by the Tlingit, so that one clan may be perceived to have more of a right to a particular crest than others. Because crests were so closely linked to a group's identity, and because other clans validated one's own right to a crest, wars occasionally resulted from attempts by competing clans to gain status over the other: to become the highest ranking owners of the crest. Appropriating a crest sometimes forced the payment of a debt or it intentionally shamed a rival clan. This was in part due to the fact that these objects were group property; they could not be transferred, conveyed, or alienated unless all members of the clan agreed. Clans sometimes possessed the use of more than one crest. Wealth, of course, played an important role in the number of crests a house or clan could own, since "some families were too poor to have an emblem, and on the other hand it is said of some of the great ones...that they were so rich that they could use anything." The social functions that crest objects served, however, are inseparable in Tlingit thought from their role as sacred objects. Clan crests both symbolize the spirit of the being depicted on objects and embody the spirit that resides with them. Crests symbolize kinship and a spiritual relationship of its clan members to the physical wildlife, and they bond the Tlingit to their ancestors who paid for the crest with their lives or deeds by holding the object through the generations. As crests and crest objects served to unify the people to their

ancestors, to each other, and to the natural forces around them, the

Tlingit treated them with great respect and reverence, for it was

through them that they defined themselves. Although the Tlingit did not

worship crests or the creatures they represented, they did cast

spiritual meaning to the people and crests were represented on a wide

variety of a clan's objects and in many different materials, including

blankets, tools or weapons, crest (totem) poles, rock art, hats, body

art, and tattooing kits. All crest objects were made by a member of the

opposite moiety and at the first potlatch or ceremonial party, the

public display and witness of the crest by the attendees imparted great

value to the object. The guests were appropriately compensated for their

attendance because it validated the prestige and importance of the crest

object, especially if it were the newly tattooed body of the Tlingit

host's son or daughter.

TLINGIT AND HAIDA TATTOOING PRACTICES Tlingit and Haida tattooing was performed in conjunction with the potlatch. Generally speaking, potlatches were typically held to honor the dead and their exploits, but they also served to enhance the prestige of the living. Tlingit individuals of rank were greatly concerned that others should recognize their clan's claims, status, and history. For the purpose of maintaining the clan's standing, the clan hosts publicly distributed great amounts of property at the potlatch, both tangible and intangible, which was necessary to validate and uphold the social ranking and position of the clan and its leaders relative to other clans in Tlingit society. Names, ranks, privileges, and honors of the lineage inheritance were meaningless without this formal ritual of hospitality and the acceptance of gifts by the guests:

Potlatching was a method of publicly acknowledging and validating a clan's status during memorial and other rites. The costs associated with the distribution of property were great, especially as a thousand people might be in attendance at any one time. Groups of related families mustered all available resources to make the occasion memorable, for their standing and influence in the tribe depended on such display and wealth. Oftentimes they erected a lasting symbol of the occasion - a totem pole. However, other types of potlatches were given by very wealthy chiefs to enoble their children. These ceremonial events, practiced by both the Tlingit and Haida, were primarily held for the oldest child, although other children of the same house or lineage were included. For major potlatches of this kind, guests belonging to the father's moiety, but of different clans, would be invited from neighboring villages or tribes. After several days of feasting and dancing, guest chiefs or noble women pierced the ears of the children and tattooed their bodies. According to Olson, the Tlingit followed a ritualized pattern when it came time for the piercing and tattooing of the noble children at the potlatch:

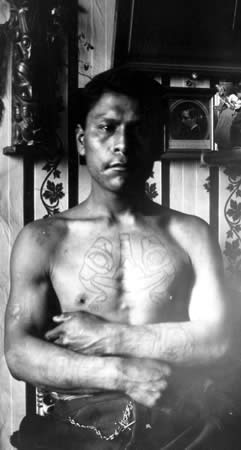

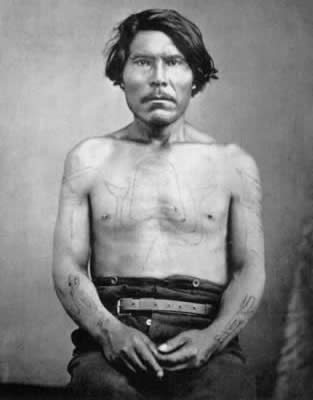

George T. Emmons, a knowledgeable collector and fastidious observer of Tlingit culture who also served as an officer in the U.S. Navy in the Alaska Territory from 1882-1896, recorded that these tattoos generally represented the whole body or some part of the crest animal of the clan. They were emblems of rank and expensive luxuries which only the wealthiest could afford; especially since slaves were prohibited from tattooing altogether. One of the last Haida potlatches that featured tattooing occurred in the winter of 1900-01 in the village of Skidegate in the Queen Charlotte Islands. It was witnessed and described by the anthropologist John R. Swanton, and it followed the same ritual pattern as its Tlingit counterpart. Excerpting sections from Swanton's account:

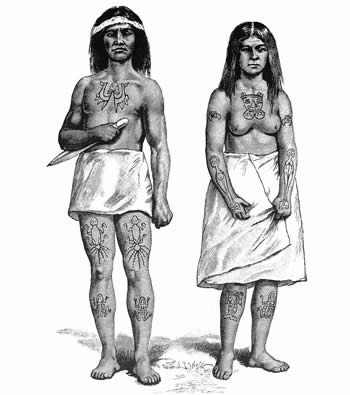

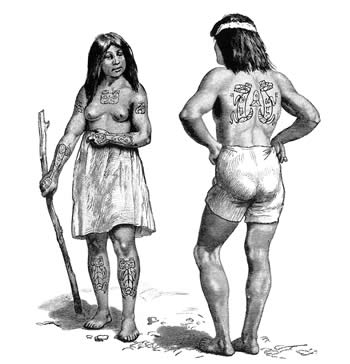

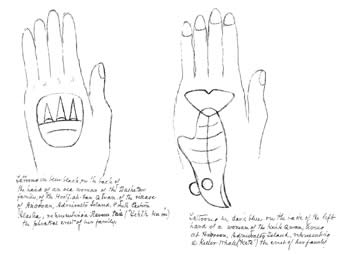

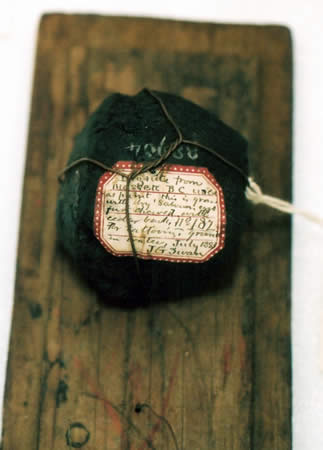

Traditional Haida tattoos (ki-da) covered the arms, chests, thighs, upper arms, feet and sometimes an individual's back or cheek. Tattooing kits consisted of a stone dish to mix magnetite (black) and hematite (red) pigments, cedar brushes with crests carved into each handle and four or five cedar batons with various configurations of needles, depending on the desired effect: shading, outlining, and fill. Before the advent of steel needles, sharp thorns, spines of certain fishes or spicules of bone were used. Thomas Lockhart of West Coast Tattoo in Vancouver, British Columbia has demonstrated that Haida tattoo instruments resemble those of contemporary Japanese hand-poking tools:

Among the Tlingit similar tools were used, but only after contact with European traders: "After the acquisition of trade needles, a pricker was made with four of these placed close together in the end of a wooden handle." This pricker replaced the more traditional Tlingit tattooing tool - a simple bone needle and piece of sinew thread. Although we have no eyewitness accounts of Tlingit skin-stitching, linguistic evidence supports the view that the Tlingit previously "sewed" in their tattoos with needle and thread. The old word for tattoo is kuy-kay-chul meaning "sewing on the body." Although painful, skin sewing was a widespread method for tattooing, especially among more northerly Arctic peoples who practiced it for over three millennia. SOURCES |

|||

|

Other tattoo articles by Lars Krutak

|

|||

| Celeb Tattoos | Facts & Stats | Designs & Symbols | History | Culture | Links | Tattoo Galleries | Contact | |||