Marks of Transformation:

Tribal Tattooing in California and the American Southwest

Article © 2010 Lars Krutak

Sinkyone men also wore “tattooed necklaces.” Although no reason was given for the custom, it appears that such designs were expensive by local standards and indicated that the owner was a man or woman of high social status. For example, similar designs were also worn by Nomlaki men of rank. These “persons of substance” were decorated with intricate bands of tattooed triangles on their necks and upper arms, and these same designs were also carved into their hunting bows. Apparently Costanoan women illustrated by Choris about 1810 also wore these designs and probably carried similar social meanings.

|

|

|

Costanoan. Heavily tattooed woman with geometric neck, arm and chin tattoos, ca. 1810. |

Yurok. Women with various chin tattoos, ca. 1890s. |

Yurok. Women with various chin tattoos, ca. 1890s. |

Among the Shasta, Achumawi, Atsugewi, Klamath, Maidu, Wintu, Karok, and Tolowa deer hoof dance rattles were given to female initiates to frighten away evil spirits. And around Maricopa, Diegueño, Kamia, and other tribal campfires various songs and dances were performed by community members to purify the female neophytes, to secure “spiritual power,” and to fortify and prepare them for womanhood.

|

|

“Blood Magic”

Although little is known about the experiences of women in menstrual seclusion outside of indigenous society, the various assortments of menstrual taboos recorded in ethnographies of autochthonous peoples almost universally characterize menstruation as a definitive form of pollution. However, menstrual taboos, rather than protecting society from the universally ascribed feminine evil of pollution and disruption of the social order by evil spirits, can perhaps be better understood as something more positive. One important example of the positive attributes of menstrual seclusion has been documented for the Yurok. |

Among the Yurok of California, it has been made explicit that menstrual taboos and seclusion protected the creative spirituality of menstruous women from the influence of others in a more neutral state as well as protecting the latter from the potent, positive spiritual forces ascribed to such women. Yurok women viewed seclusion not only as a means towards spiritual ascendancy but also as a way to enjoy a break from their normal labors around the household and agricultural fields. While in seclusion, they wove and enjoyed the camaraderie and gossip of other women. And as Buckley illustrates in his work on menstrual “Blood Magic,” menstruating Yurok women isolated themselves:

Because this is a time when [they are] at the height of [their] powers. Thus the time should not be wasted in mundane tasks and social distractions, nor should one’s concentration be broken by concerns with the opposite sex. Rather, all of one’s energies should be applied [for ten days] in concentrated meditation “to find out the purpose of your life,” and toward the “accumulation” of spiritual energy. The menstrual shelter, or room, is “like the men’s sweathouse,” a place where you “go into yourself and make yourself stronger.” As in traditional male sweathouse practice [ten days], or “training” (hohkep-), there are physical as well as mental aspects of “accumulation.” The blood that flows serves to “purify” the woman, preparing her for spiritual accomplishment. Again, a woman must use a scratching implement, instead of scratching absentmindedly with her fingers, as an aid in focusing her full attention on her body by making even the most natural and spontaneous of actions fully conscious and intentional: “You should feel all of your body exactly as it is, and pay attention.”

| There is, in the mountains above the old Yurok village of Meri·p, a “sacred moontime pond” where in the old days menstruating women went to bathe and to perform rituals that brought spiritual benefits. Practitioners brought special firewood back from this place for use in the menstrual shelter. Many girls performed these rites only at the time of their first menstruation, but aristocratic women went to the pond every month until menopause. Through such practice women came to “see that the earth has her moontime,” a recognition that made one both “stronger” and “proud” of one’s menstrual cycle.

[I]n old-time village life all of a household’s fertile women who were not pregnant menstruated at the same time, a time dictated by the moon; that these women practiced the bathing rituals together at this time; and that men associated with the household used this time to “train hard” in the household’s sweathouse. If a woman got out of synchronization with the moon and with the other women of the household, she could “get back in by sitting in the moonlight and talking to the moon, asking it to balance [her].” |

|

Wukchumni. Young girls who were close friends often had themselves tattooed at the same time by an old woman. The pattern was marked on the person with the charred end of a sharpened stick. The lines were then abraded with a small arrowhead, and a paste of grease and charcoal was lightly rubbed in.

Shastan groups also utilized grease in their tattooing, but they cut-in their tattoos with flint and employed soot specifically obtained from the sweathouse hearth and mixed it with bear grease.

The purpose given for Wukchumni tattooing was beautification, and also the belief that it prevented one from getting old and wrinkled: the Pima of Arizona maintained the same belief. One form of tattooing, however, was reported to have religious significance, and only a few examples have been observed by early writers who also witnessed such markings on Yokut women and Mono men. This tattoo consisted of a small pattern placed on the inside of the right forearm just above the wrist and was said to the location one one’s “supernatural power” and perhaps their “totem.”

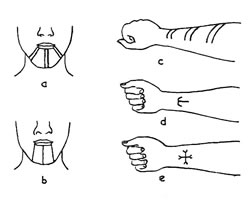

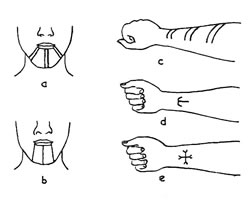

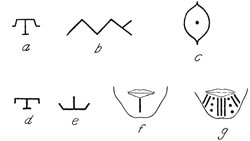

Of course, some Yokut women also had tattooing placed on their thighs, while others were observed with several chin stripes that continued downwards to the neck and thence into zigzag lines appearing on the chest, breasts, and thorax [FIG]. These practices have also been documented for the Eastern Miwok, Pomo, and Patwin among others. |

The “Roasting” of Girls

On the other hand, first-time menstruants among the Pomo, Miwok, Tubatulabal, Cahuilla, Maricopa, Luiseño, Diegueño, Havasupai, and to a lesser degree the Konkow of northern California, observed “roasting” rites in addition to the seclusion.

On the first day of a Luiseño girl’s puberty ceremony (Wukunish), the menstruant was placed in a heated rock pit. On top of the stones was a layer of brush which the girl reclined upon for a period of three days and nights. Except for brief feeding periods of vegetable products (meat and fish were tabooed), the girl lay covered in the pit which was continuously surrounded by a procession of dancers and singers. Then, the menstruant received counsel from an elder who, among other things, said: “And you will roast yourself at the fire (after childbirth), and then your son or daughter will grow up quickly, and sickness will not approach you”.

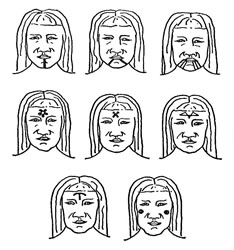

After all such private ceremonies had reached their climax (e.g., fasting, singing, dancing, and “roasting” rites) menstruants participated in a public ceremony of tattooing. Here elder women worked as the tattooist decorating the chin of the initiates and then rubbing the wounds with carbon-based pigments which had perceived purificatory properties. In turn, the menstruant – as initiate – became permanently incorporated into maternal society by her chin markings, and these tattoos symbolically solidified her physical transformation into a reproductive entity. |

|

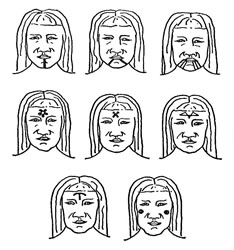

Walapai. Women’s facial tattoos, 1928. Local informants reported that some of the tattoo designs worn by the Walapaai were copied from petroglyphs, and that “children frequently pinned down some boy or girl whom they did not like and tattooed them.” Apparently, unwanted tattoos could be removed “by applying a piece of watermelon, which is allowed to decay six or seven days.” |

The Diegueño Atanuk, or girls’ puberty ceremony, closely corresponds to the Wukunish of the Luiseño. Several girls undergo the ceremony at the same time and were either disrobed completely or wore short skirts of willow bark fastened with belts of milkweed fiber. A pit was dug, large enough to accommodate all of the girls when stretched out at full length. This excavation is lined with stones and a large fire kindled in it. When the stones became very hot, the fire was removed and the pit filled with green herbs. Three kinds are used: white sage, thistle sage, and common ragweed. The girls were then brought to the edge of the pit and seated, in the presence of all the people of the village. At a signal the entire company motioned upwards three times, expelling their breath each time. Then, the leader filled a basketry cap with water, and mixed in it crumbled native tobacco. Each girl takes a large drink of the liquid. If there was anything evil in the girl, this drink, it was thought, would cause her to vomit it out, and she would never be troubled again. After the girls imbibed this mixture, they were placed at full length, face-downward on the bed of herbs, and covered with a blanket of rabbit skin. Sage brush was then piled over them. The heat of the rocks produced a fragrant steam that enveloped the girls. The steaming was continued by renewing the herbs and adding new hot rocks. The girls remained in the pit and moved as little as possible until they could no longer withstand the strain of confinement. The roasting usually lasted about one week, though girls who were not of a nervous disposition attempted to endure the cooking for three or four. The longer the confinement, the greater the benefit was supposed to be.

A ceremonial crescent-shaped stone (atulku) was warmed at the fire and placed in turn between the legs of each girl close against her body. The supposed effect was to warm and soften the abdominal muscles. The quality imparted by this stone was thought to last throughout one’s lifetime, and to make future motherhood easier for the girls. A garland or hat of ragweed wrapped with tule reed was later placed on each girl’s head. This garland was renewed every day while the girls remained in the pit. They also wore on their wrists, throughout the roasting, bracelets made of human hair. Their faces were painted black each morning with a “straw-colored” charcoal. |

|

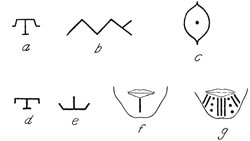

Havasupai. Men’s and women’s tattoos, ca. 1910. A-E center of man’s forehead; F-G, female chin designs. |

Next Page |

1

|

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

Museum photo gallery of the images

on this page may be seen here. |