Marks of Transformation:

Tribal Tattooing in California and the American Southwest

Article © 2010 Lars Krutak

Identification & “Money” Marks

Other Hupa tattoo marks were related to other forms of measurement. Because redwood was not available in great quantities in their home region, the Hupa imported all their canoes from the lower Klamath. Some standard of measure was required to estimate the size and relative value of each watercraft. The canoes were quite uniform in length, being about eighteen feet outside measure, but varied in width and depth with the size of the tree from which they were made. Around 1900, old Hupa men of the tribe possessed a series of marks tattooed on their legs similar to those on the arms by which money was measured. By means of these, the height of the canoe was easily estimated. In fact, almost every article manufactured by the Hupa was made in reference to their tattooed lines or to some part of the body as a unit of measurement.

|

|

|

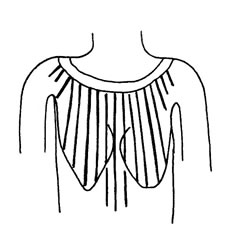

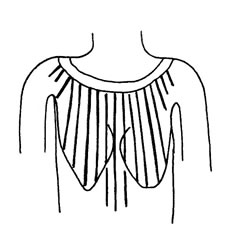

Yokut. Marked examples of Yokut tattoo designs were observed among two very elderly Chukchansi or Northern Valley Yokut women by C. Hart Merriam in 1902 near Coarsegold, California. He stated: “In one [camp] was a blind old man and three very old women. Two of the women were elaborately tattooed, and on payment of two-bits each pulled off their shirts and showed me their body decoration. The simpler of the two consisted of two broad rings low down on the neck or upper breast, from which broad straight lines ran down between and over the breasts. All of the markings are broad, about one-half inch wide. After I had examined this one, the other pulled up her shirt and [displayed] her thoractic and abdominal decorations [that] were most remarkable and complicated, and far more elaborate than those of the other woman. There were numerous cross bands and rings and short vertical lines and short vertical lines and circles and all sorts of things, but she would not let me make a diagram or take a photograph, so I could not record the wonderful things. They had a number of vertical and oblique tattoo lines under the chin and one had curious markings on her arms.” |

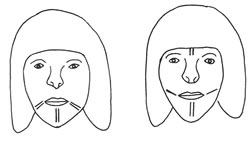

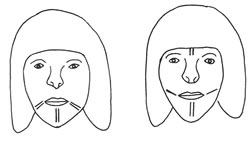

Yokut. Tattooed women seen on the Fresno River (left) and at Picayune (right), 1900. |

Marks of Transformation

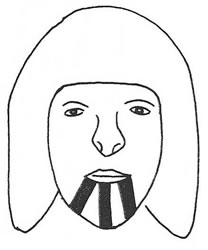

Although the tattooed bodies of men and women in the American West have long since faded away, there is news that these indelible traditions are beginning to take root once again. Today, traditional tattooing is making a comeback with some northern California people like the Yurok and their neighbors. And about two dozen women from these and other tribes like the Klamath reportedly bear the “111” tattoo on their chins.

|

|

Keone Nunes, a Native Hawaiian tattooist who is widely considered to be one of the foremost traditional hand-taping tattoo artists working today, has helped spearhead this revival.

|

California Tattoo Renaissance. Keone Nunes tattooing a Yurok Woman, 2002. Photograph courtesy of Keone Nunes. |

Lyn Risling, who is of Hupa, Yurok, and Karuk heritage said, “It’s like wearing your culture on your face every day.”

One writer, who observed Risling’s recent tattoo session, likened the tattoo’s transformative power to a rebirth; one that was also experienced collectively and individually by countless generations of indigenous men and women in former times:

“As the tattoo slowly spread across Lyn’s chin, we all felt the exact moment when the transformation occurred. It was a startling and beautiful moment that brought tears to our eyes. The shared pain and joy reminded us all of a birth. The painful, bloody time had passed, and now there was a new person in our midst.” |

|

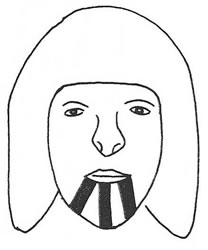

Karuk.Women’s facial tattoos, 1900. |

Literature

Buckley, T. (1988). Blood Magic: The Anthropology of Menstruation (T. Buckley and A. Gottlieb, eds.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Choris, L. (1822). Voyage pittoresque autour du monde, avec des portraits de sauvages d’Amérique, d’Asie, d’Afrique, et des îles du Grand Océan…Paris: Firmin Didot.

Gifford, E.W. (1936). Northeastern and Western Yavapai. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 31(5): 257-334. Berkeley.

Goddard, P.E. (1903). Life and Culture of the Hupa. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 1(1). Berkeley: The University Press.

Goldschmidt, W. (1951). Nomlaki Ethnography. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 42(4): 303-443. Berkeley.

Heizer, R.F. [ed.] (1978). California. Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 8. Washington: Smithsonian Institution.

Hostler, A. (2006). “Taking It on the Chin.” www.reznetnews.org/culture/051121_tattoo/

Kroeber, A.L. (1925). Handbook of the Indians of California. Bureau of America Ethnology Bulletin 78. Washington. (1935). Walapai Ethnography. Memoirs of the American Anthropological Association 42.Menasha, Wis.

Krutak, L. (2007). The Tattooing Arts of Tribal Women. London: Bennett & Bloom.

Mifflin, M. (2009). The Blue Tattoo: The Life of Olive Oatman. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Nomland, G. (1935). Sinkyone Notes. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 36(2): 149-178.

Ortiz, A. [ed.] (1983). Southwest. Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 10. Washington: Smithsonian Institution.

Powers, S. (1877). Tribes of California. Contributions to North American Ethnology 3. Washington: U.S. Geographical and Geological Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region.

Russell, F. (1908). The Pima Indians. Pp. 3-389 in 26th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology for the Years 1904-1905. Washington.

Spier, L. (1928). Havasupai Ethnography. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History 29(3): 81-392. New York.

Taylor, E. and W.J. Wallace (1947). “Mohave Tattooing and Face-Painting.” Southwest Museum Leaflets 20: 1-13.

Waterman, T.T. (1910). The Religious Practices of the Diegueño Indians. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 8(6): 271-358. Berkeley.

First Page |

1

|

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

Museum photo gallery of the images

on this page may be seen here. |